Colin Jones was at his peak in 1982, the European title was now in his sights; a fight against the classy Hans-Henrick Palm was arranged and Jones’ team had secured home advantage. Unfortunately, Jones fell ill on the eve of the fight; his pallid appearance on the day of the contest forced manager Eddie Thomas to bring in a doctor. There was to some bad news, Jones was suffering from Appendicitis. Jones would have given anything, even his health, to fight that night—there was more than just a title at stake:

“I would have boxed had I got past the doctor,” he said. “I had just bought a new house and I needed the £17,000 we had signed up for at the time. I would have boxed, yeah, why not? Luckily, looking at it now, the doctor stepped in, and I was glad of that. They only had to look at me to know what was wrong, I was yellow.”

Hand problems—the puncher’s burden—also hindered Jones, but he shrugged them off as “Part and parcel of the game.” The fight with Palm was rescheduled. Jones had to travel to Denmark, home town advantage was gone but he did not care, his pre-fight preparation was given a boost as welterweights could wear six ounce gloves back then.

“(The) left uppercut is a bread and butter shot when someone is in no fit position to defend himself. It comes right through the guard and does the trick.”

“Yes, I insisted on the six ounce gloves—there was a choice, eight or six ounces—although bag mitts would have been fine by me—but we took the six ounce gloves and knocked him out,” said Jones. “If I had been wearing eighteen ounce gloves he would have got the same treatment.”

It was Jones’ night that night, he was at the very pinnacle of his game. Palm did not stand a chance, he was brushed aside in two rounds. When Jones talked about the fight there was the slightest hint of regret, he liked Palm.

“Yes, I think that was my night, every fighter gets one of those nights, if you are very lucky you get two—I would have given anybody in the world trouble that night,” he recalled. “He was a hell of a nice chap you know, Palm.

“You don’t think about that at the time so you throw your shots, the ref could probably have saved him though. I had caught him with a great shot initially, a left hook to the head [the shot put Palm down]—(it) put him in terrible trouble. The ref should have saved him.

“Palm never boxed after that, the poor bugger—he had trouble with his retinas—and if you see the tape you can see why he never boxed again. He was a smashing guy. I bumped into him in Denmark last year. He is doing quite well, so good for him.”

Palm got up from the first left hook, only to be felled by a right uppercut. He got up again, so Jones ended his resistance with a trio of left uppercuts, knocking Palm’s head about with the shots. For Jones the use of this punch is the sign of a serious finisher, he said: “That left uppercut is a bread and butter shot when someone is in no fit position to defend himself. It comes right through the guard and does the trick.”

He added: “We had read about Palm before the fight and we had seen his record, he had beaten nine of our boys before that. We thought it would be a bit more of a rough ride, but that was my night and, unfortunately, he had to be on the end of it.”

A boxer must yearn for another fight after putting a performance like that; a chance to jump back in and mine that rich vein of form—the Palm job was over too quickly for Jones’ liking:

“It would have been nice for everyone if I could have jumped into the ring again and fought someone else that night, wouldn’t it? In the real world you have to go back to the gym, and get back on the grindstone.”

Jones’ British, Commonwealth and European title successes had brought him a Number Three ranking in the WBC top ten. His reward was an away-day date for the vacant title against the flashy Kronk fighter Milton McCrory.

“The way I looked at it—after we had the offer from Mickey and the higher offer from King—was that I could hit him (Milton McCrory) on the chin in Nevada or I could hit him on the chin in Wembley, with the same result. I had no fear of going to fight anyone in their own back garden. I brought my own judges and referee (my fists).”

Jones ceded home advantage after Mickey Duff’s bid for the contest was dwarfed by a counter offer from McCrory’s promoter Don King. Colin recognised then, as he does now, that boxing is a business; he had no fear about going away to Reno for his first world title shot.

“The way I looked at it—after we had the offer from Mickey and the higher offer from King—was that I could hit him on the chin in Nevada or I could hit him on the chin in Wembley, with the same result,” he recalled. “I had no fear of going to fight anyone in their own back garden. I brought my own judges and referee (my fists).”

McCrory was cast from the Tommy Hearns mould, a physical replica of the ‘Motor City Cobra’ minus the devastating one-punch power of Hearns. For Jones, though, the only thing that can prepare you for a fight is the fight itself, to that end he never bothered seeking out tapes of McCrory.

“Never saw a tape of him, never,” admitted Jones. “That (getting tapes of fights) wasn’t the norm back then. I decided that I would see what he (McCrory) had in the early rounds, have a word with Eddie and Gareth (between rounds) and take it from there. If you speak to the boys from my day you will find that this was the case for most people. I fancied the job but 12 rounds [the scheduled distance of the fight] are different than 15 rounds. Give me fifteen rounds and things might have been different. Things weren’t meant to be.”

Jones started slowly. McCrory was boxing beautifully at times in the middle rounds only for Jones to land some big bombs. In the ninth, the visiting co-challenger broke through with a clean left hook, McCrory was all at sea—it was the Kirkland Laing fights all over again.

“It probably looked like that from the outside, but when you are in the fight you don’t think about stuff like that, you don’t think about what round it is,” he said. “I probably didn’t realise how much I had him going until I saw the tape afterwards. I didn’t sense it in the fight itself and couldn’t explain to you why (that was). I normally could see the winning post and nail a guy.”

McCrory’s early lead had been chipped away, though. Milton recently claimed that this contest, and the rematch, hinged on the final rounds. McCrory rallied in rounds 10 and 12, and looked to have nicked it at the death. The judges differed, calling it a draw. Jones also felt that the last round had decided the fight.

“Eddie told me that it was close so it was a typical last round; he had greater hand speed than myself and he used that, he used it well.”

The Reno crowd had taken to Jones, cheering him on throughout the fight, whilst, sporadically, booing the backwards movement of McCrory. A rematch was mandated. Jones travelled to American for a second time. The return was held in Las Vegas in the afternoon and amid stifling 100 degrees heat.

Jones came out looking to, again, feel his way into the fight only for a counter left hook to drop him at the end of the first round. Jones shook his head when reminded of this. “It was totally alien for me to be on the deck in the first round of a fight, or any round for that matter, because I’d never been down before,” he said.

“It was a new experience for me. I remember looking at the corner. Eddie told me to get up at eight or seven. There was no danger of me being knocked out, but I was now trying to make sure I didn’t get a conk on top of that one.

“I went back to the corner and sat down, Eddie asked me if I was OK. I told him that I was having trouble seeing, Eddie said: ‘Oh, you can’t see then, can you? Then how the hell did you find your way back to the corner?’ That was the most compassion you got from Eddie, he just started sponging me down.

“I will remember that for the rest of my life, you know, him saying: ‘Get your arms up, keep hitting him and keep plugging away’. There was no need for a change in tactics. I was a come forward fighter and had to keep on going.

“I felt a bit more comfortable in the second fight, to be honest. I knew what was coming, these long, looping shots, and there was the same pattern (as the first fight). I thought he was flat in that second fight. I think I had him going again in the seventh and ninth, but he came out fresh as a daisy in the 10th. Not many people had come back at me after a couple of tough rounds.”

“You hear a lot of people losing fights and saying things—it sounds like sour grapes. I made the choice to go to America for those fights. To be honest it was a case of such a big purse, or two, that I didn’t really have any option, so I took it. I didn’t get the nod, and that was it.

However, the American came on again as the fight progressed, making a final stanza stand. It was a carbon copy of the first contest only with a different outcome as McCrory was awarded the title on a split-decision. Jones’ dream had died, and there would be no excuses.

“You hear a lot of people losing fights and saying things—it sounds like sour grapes. I made the choice to go to America for those fights. To be honest it was a case of such a big purse, or two, that I didn’t really have any option, so I took it. I didn’t get the nod, and that was it.

“I had respect for him (McCrory) as a fighter. I never spoke to him after the fight, but I met him when I went over to Las Vegas for the Barry McGuigan–Steve Cruz fight. I spoke with Milton briefly for five minutes in the casino and we said a few words in parting. We were still fighting, so I didn’t like him back then and he probably didn’t like me. We could have fought a third time, you had that in your mind.

“With that said I met him last November when we took four young lads to an amateur tournament in Canada—it was a good little event. Obviously, I had mellowed tenfold by then. You have time to reflect on the two fights you had, and we did that when we met up [Writer’s note: I asked Colin if they had sat down and watched reruns of the fights together]. No, I had seen enough of them by then (laughs). Milton’s structure was deceiving. I thought he would crumble like a bag of bones but he didn’t.”

King had secured more than home advantage when bidding for the fight, he made sure that it took place in the afternoon. Ironically, the sweltering heat seemed to hit McCrory harder than it hit Jones, who smiled when asked about the weather conditions.

“I thought he would be climatically more conditioned for the weather, more so than a Celt, but that wasn’t the case,” he said. “I had great preparation for that fight, a fortnight in Lake Tahoe then we dropped into Vegas for the last two weeks, training at Johnny Taco’s gym. It was the best I had ever prepared so I can’t say that it was the weather that beat me, I have to say that it was the opponent himself.

“Boxing is a long old track, I had been on it from the age of nine, and was now 24. I felt that I had failed and would never get another crack—I thought that I would just be fighting 10 rounders for a while.”

McCrory took over a pocket of British support for the McCrory fights. Colin was a paid up member of his local miners’ union. The miners were facing tough times, and things would get worse. Still, the miners scraped together the funds needed to support their hometown hero. Jones’ adventures were a welcome relief from the politics of the pits, he told me that:

“Me and my brothers had all been miners and they were suffering hard times, a lot of them travelled to support me. It cost about a thousand pounds, which was a lot of money. I guess they thought that this type of thing doesn’t come around too often, so they did everything they could to support me. The majority of people were miners in those trips [Writer’s note: they gave something back to the miners when granting them half-price entry to Jones’ 1984 fight against Billy Parks].

“I was once a digger in a graveyard and had been in the mines for two years. Eddie had a mine so I worked in that one for him. People loved the gravedigger angle. They would have me standing in graveyards on top of a box and all that nonsense.”

It is the norm in boxing for a losing boxer to switch things around; for Jones, though, there was no question of leaving Thomas, who had guided him from the start and was a local man. As Jones explained:

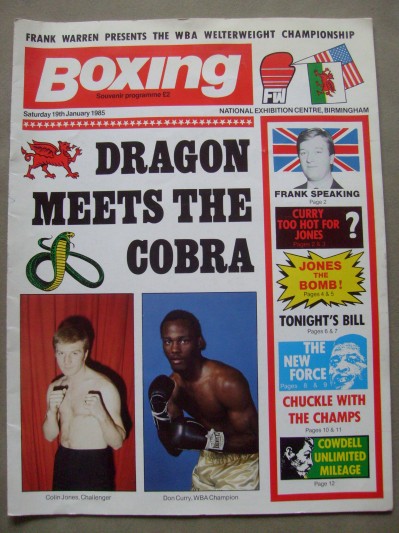

“No, leaving Eddie or Gareth never crossed my mind. I am a big believer in loyalty, which is something that is missing in sport in general these days. I feel sad to see these lads without any loyalty. After the title losses Frank (Warren) came along and got me two 10 rounders in 1984, and then got me the Don Curry fight (in 1985).”

The first of those 10 rounders came against Allen Braswell, Jones was greeted with a rousing standing ovation, the Welsh crowd sang Hen Wlad fy Nhadau (Land of My Fathers)—it was hair-raising stuff. However, there was a softness about Jones in that fight, he no longer looked like he had been hewn from rock. Despite this Jones registered a second-round KO win.

“People thought (Billy) Parks would crumble after five or six rounds but he was a tough old cookie. I picked up a couple of nasty cuts in that fight. I wasn’t in love with the game anymore by that point. You wake up in the morning, see the bad weather and think: ‘Another hour in bed’—it is your body’s way of telling you that you are no longer there (at your peak).

However, that soft look was in Colin’s face, and eyes, for his next assignment, a fight with US-based McCrory look-alike Billy Parks. Jones, who, unusually for a white boxer, had not been troubled by skin problems, suffered a terrible cut alongside his right eye, courtesy of a left hook (ironically enough Parks had the expert cuts man Mick ‘The Rub’ Williams in his corner).

Parks led Jones a merry dance at times, befuddling Colin with movement, then blasting through the Welshman’s guard, it was a rough night’s work yet Jones stopped his man in the 10th round, a pair of right hands leaving Park wobbly-legged.

“That was a hard old fight that was,” said Jones, a wry smile breaking out across his face. “People thought Parks would crumble after five or six rounds but he was a tough old cookie. I picked up a couple of nasty cuts in that fight. I wasn’t in love with the game anymore by that point. You wake up in the morning, see the bad weather and think: ‘Another hour in bed’—it is your body’s way of telling you that you are no longer there (at your peak). I was still prepping well but was showing the signs of a long time in the game without a break.”

“They leave their mark, those hard fights. No fighter gets away with two tough fights like the McCrory fights—it takes years to get the memory out of your system.”

Jones was once again on the cusp of a world title fight, with WBA/IBF boss Curry his chief target. In the meantime, Jones needed to deal with the torn skin around his eyes. Jones sought out expert help after the Parks contest, having his scar tissue worked on by a top plastic surgeon.

“Yes, that is true, they didn’t heal properly so I went to Harley Street to get the scar tissue taken away,” revealed Jones. “There was a lot of pink scar tissue and I wanted to carry on for at least another year, so I can assure you that it wasn’t cosmetic surgery.”

You would naturally expect a boxer to worry about scar tissue after suffering cuts in his last fight, for Jones, though, there was a bigger worry going into the Curry contest: he was no longer in love with his trade.

“I don’t think they (the cuts) affected me or my approach. I was tired with the game. I got into great shape for that Curry fight but it was a case of falling out of love with something. I had gone hard at it. I had lived in the gym and had loved living the sport, but unfortunately, by that point in my career, I had fallen out of love with boxing.”

Hopes of a Jones win were based on Jones’ punching power, which was still top class, and the whispers circulating about Curry’s struggles with the scales. Don allegedly abstained from food for a full day during fight week, a cup of tea and some chewing gum his only sustenance according to Sports Illustrated.

“I would never get another chance so it just came out all at once (as a scream after losing to Curry), I imagine—all the frustration and disappointment. I think it was the frustration of still having so much left to give that got me. I was sad to lose my record of not being stopped. There was obvious disappointment at the time, but you soon get over it.”

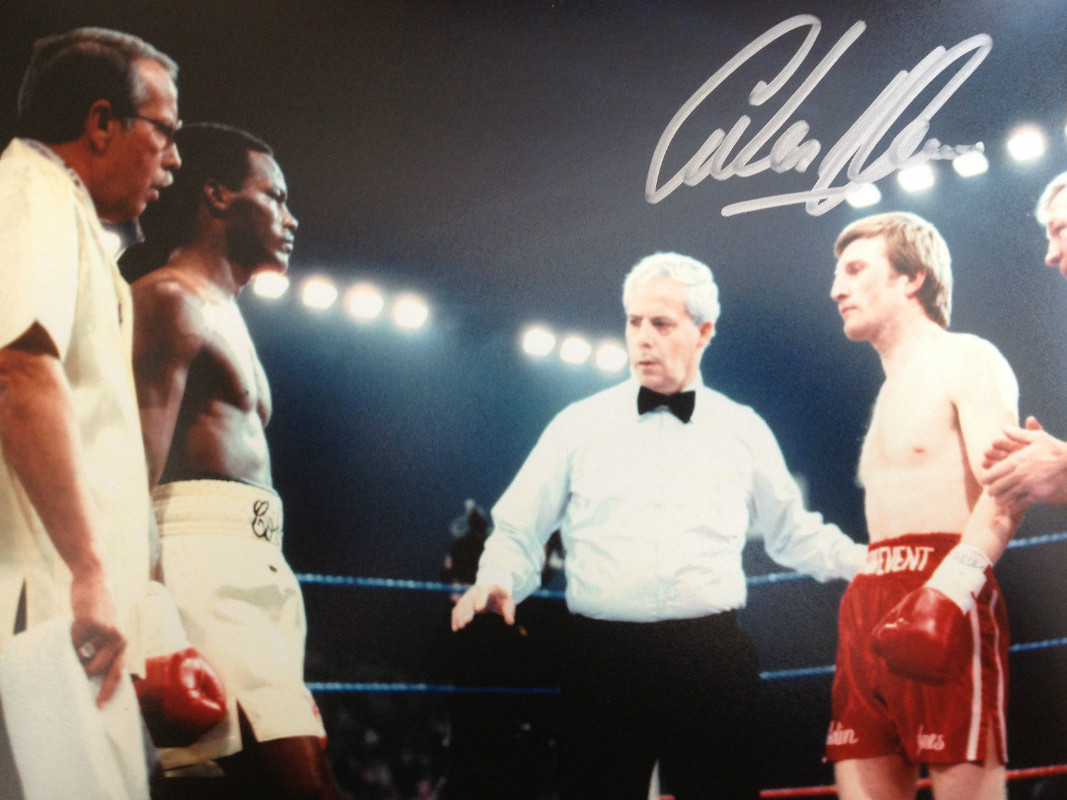

Despite this Curry was every inch the budding superstar in the fight itself. Upon realising that the ring was too soft for excessive moving and boxing, the champion elected to stand and fight. Jones had suspected that this may be the case.

“I knew about Curry, I had read about him—a good crisp combination hitter—but there was nothing different about prepping for him. You never know what to expect on fight night. I knew he could move and throw class combinations, but I knew he couldn’t hurt me, and in that respect the cuts and the bruises I suffered were just a nuisance. I wasn’t rocked or frozen.”

One of those cuts (a horizontal Mars bar across the bridge of the nose) heralded a critical moment in the fight, and Jones’ career. It was clear that Jones now needed to score a knockout in order to win the world title, and, looking back, the fighter still feels that there was a tangible possibility of that happening.

“Eddie told me it was a bad cut (at the end of round three) and that I had to make the most of the fight while it lasted. I still don’t think that Curry was a real mover, he stood and traded with the best of them—and that was all right by me at that point. I didn’t know how bad the cut was until I saw it from the outside. It was a bad one, wasn’t it?

“I think the cut itself was an accumulation of three or four punches [a left uppercut followed by a few jabs]. The referee said: ‘Stop boxing’ in round four, and the doctor stopped the fight. I had a couple of stitches afterwards, and that was it.”

Jones sagged into the ring post when told that his title bid was over, a shot of him howling with frustration was voted one of the images of that sporting year. Jones was disappointment personified in the post-fight interview.

It was not just the loss that rankled, it was the manner of the loss. To lose without giving it his all was a cruel experience for Jones, cut or no cut he had wanted to fight to the finish; he knew that his last chance for a world title had slipped away.

“Oh yeah, I knew that was my last chance at the ultimate prize,” said the softly spoken former fighter. “I would never get another chance so it just came out all at once (as a scream), I imagine—all the frustration and disappointment. I think it was the frustration of still having so much left to give that got me. I was sad to lose my record of not being stopped. There was obvious disappointment at the time, but you soon get over it.”

Jones ran into a fighter, Curry, who was at the top of his game, at a time when his own desire was on the wane. Throw in the weakening of his skin and it was a big ask, one that was beyond Jones at that point.

“Yes, that is a fair comment, and a fair way to look at it,” he said. “It happens to all fighters and no matter how hard you might train there has got to be losers, and that was the end of the road for me. I never looked back, I continued on with my life. I always look forward and have always been involved with the game, more so now than ever.”

Oddly for such a slow-burning boxer, Jones was done with the sport at the tender age of 25 and with a 26-3-1 (23 KOs) record. There would be no comeback, no final fling; Jones went back home to the place where he had grown up, his adventure was over:

“I just did what I had done all my life. I enjoyed the working mens’ club, like my fathers and brothers before me. I had a normal life and a young family. I settled into a steady family life. I was like I was in my boxing, really—slow and steady. I met my wife when we were in school and stayed with her. I had one amateur club. I had one trainer in Gareth Bevan. One manager in Eddie Thomas. I am just an ordinary guy, really.”

When Jones retired he did what all former fighters do, he put his era into a bottle, labelling it lovingly as ‘golden’. He then watched as boxing became awash with Mickey Mouse titles. The aging former pro looked on as men with a small percentage of his talent became ‘champions’. All the while thinking: ‘I could easily have won a title in this weakened field’.

“I think all us old fellas look at how it is now and think that,” was his wistful reply when asked to compare eras. “I would have been a liar if I said I had never looked and thought ‘I could have handled him’ or ‘I could have done him’.”

As our time wound down I asked Jones if he had ever considered where he would be if he had not walked into a boxing gym, would he have been able to curb his fire without the outlet of boxing.

“Well, you have to accept that somewhere along the line it is in your system to be the person you are, to stand up for your rights, and it can get you in trouble, but boxing gave me direction. Boxing finds many people early on in life.”

Jones no longer follows professional boxing; he is exasperated with the proliferation of titles. He said: “I don’t follow boxing as much as I used to. I have lost all interest in the professional game, there are no big names in the game—that is down to too many titles and governing bodies.”

As our time wound down I asked Jones who his boxing heroes had been. The list was short, containing only two men. “I enjoyed watching Ken Buchanan from the age of nine through to 15,” he revealed.

“I used to take a lot of tips off watching Ken, but there is only one great fighter in my eyes and that is ‘The Greatest’ Muhammad Ali, he could fight a bit. I never tried to copy Ali, though, because only one person could do all that.”

Throughout the day, I had wanted to ask Jones about this ‘Greatest British boxer to never win a title’ tag. It could be seen as a backhanded compliment yet I pressed on anyway, asking Jones if he was happy when people give him that title.

“I think that has been thrown about a bit, I am not sure if it is a nice tag to have, but unfortunately, someone has to have it, so if people want to give me that tag I will accept it,” he said.

After we said our goodbyes to Jones, Big Al, my friend and fellow Jones fan, and I drove past the looming monstrosity of the Cardiff Dome (Colin works with the Welsh amateur squad at the Welsh Institute of Sport). Speeding away to the sanctity of the valleys, I thought about that unwanted tag: ‘The best British boxer never to win a world title.’

It does flatter with faint praise, so I thought, instead, it would be best to raise a salutation to Colin Jones: truth talker, puncher, miner, grave digger, one of the finest British fighters of all time, a man who deserved to become a world champion and who very nearly reached that summit.

Click here for some videos of Jones’s fights.