Errol Christie’s promising career was derailed in 1984; only three years after his ABA title win. Jose Seys brought a decent number of clean KO’s into his fight with Christie; he then ambushed Christie within the first minute at the Britannia Leisure Centre, Shoreditch. It was a massive setback, brought into focus when Herol Graham stopped Seys in Jose’s next fight, setting into motion a nine-fight winless streak for Seys.

Errol was offered around £100,000 to switch promotional stables within a year of the Seys setback, proof that people still had belief in Christie’s talent; Christie decided to stick with the people around him. Manager Burt McCarthy then moved quickly to nix a proposed British title eliminator fight with fellow stylist Herol Graham in 1985, perhaps fearing a second, more damaging defeat.

“I had all those amateur fights and had been continuously training, I never took a break. I should have taken a break before coming into the pros. I was constantly battling and ignored what my body was saying. It was falling apart through all the action that came with boxing. I was fighting for my club and then fighting for my country, plus the lifestyle you are leading starts to play its part.”

Christie regrouped from the Seys loss, rattling off seven stoppage wins in a very short time span, before entering into the fight he will be remembered for, that battle of the ages with Mark Kaylor, an eliminator for the British middleweight title that became a genuine grudge match.

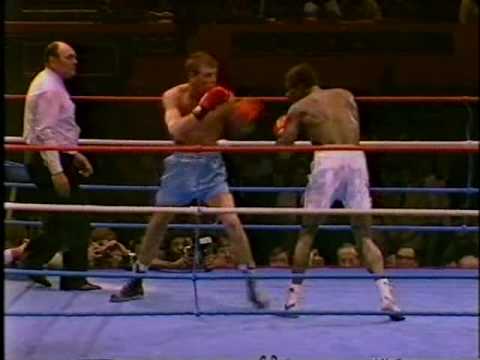

The fight itself was beautifully brutal; both men visited the canvas in round one, Kaylor was floored heavily in round three. Kaylor, roared on by the Wembley crowd, came back strong and KO’d Christie in the eighth round.

It remains one the greatest British fights ever seen. The build-up to the contest was very ugly, culminating in a brawl between the particulars at a press conference in London.

The fight was set for fireworks night 1985; there was a distinct sense that this match-up of styles would be explosive enough to befit the occasion. In order to add further spice an October press conference had been held at the Stakis casino, to further hype the fight Graham, the British Champion, and next in line for the winner, agreed to attend.

The presser saw Graham called into action early; he stepped in to diffuse a fight between Kaylor and Christie, not the first, or last, time Herol had stopped a fight breaking out.

It had all started in the courtyard of the building, Kaylor attempted to push Christie into a water fountain; a punch to the throat of Christie by Kaylor kick-started another confrontation inside the casino.

It was apparent to most that this was not a hammy attempt to shift tickets; therefore, to some, the easiest option was to suggest that the fight was now a racial confrontation. Both boxers denied this, claiming that it was a personal confrontation—these two really didn’t like one another.

On Kaylor’s part there was the feeling that Christie had shown disrespect when calling him out in the past. Kaylor claimed that he would “rip his [Christie’s] head off’ on the night. On the part of Christie, there was a feeling that Kaylor had been sitting on his British middleweight title during 1983. In truth, Errol was too young to fight for the title at this point; Kaylor then lost the title, as well as the Commonwealth belt, to Tony Sibson in 1984.

At this point it appeared that all the action we would see between the two had taken place already, that brief scuffle had thrown the bout into jeopardy and there were fears of racial tension between both sets of fans. Kaylor was said to have sold £25,000 worth of tickets, support borne of a career spent boxing in the capital, and Christie brought a contingent of Coventry fans to the party—the Coventry contingent wore ‘Keep it Cool’ shirts on the night itself.

Predictably, The Sun newspaper fanned the flames by taking a typically considered, well thought out stance when reflecting on the press conference scuffle—the “newspaper” claimed that Kaylor had provoked Christie with racist comments, and, further, that elements of the Kaylor support would make this into a racially charged night. Christie, once again, denied that the scuffle had been a racially charged one. The Sun reporter who submitted the story allegedly asked for his byline to be removed, and it was, due to the fact that his original submission had been rewritten to include the racial angle.

Promoter Mike Barrett was fearful over whether the contest would take place. The police presence was ramped up, the bar was closed, and, in a frank admission, Kaylor’s handler Terry Lawless revealed that he had asked members of London football firms to walk amongst the crowd telling people to behave. As for the press conference brawl, Lawless was again bullish, claiming that he had often seen MPs going for one another in heated moments.

There was another element to the fight. It was a showdown between ‘The Cartel’ and those outside of the Cartel. Terry Lawless, Mickey Duff, Jarvis Astaire and Mike Barrett represented The Cartel; in Christie’s corner we had Burt McCarthy, who was linked to upcoming promoter, and current force, Frank Warren.

Never one to miss a trick, Barrett issued a pre-fight poster that featured an intense stare down between the two men, the photo had been taken, you guessed, it shortly before the press conference had erupted into mayhem. It all seems a bit knockabout, and certainly the presser dust-up was probably a case of overheated boxers reacting to one another; in reality, though, Christie did have cause to fear that there would be a racial element amongst the crowd.

In the end, the Kaylor-Christie bout had the natural crowd diffuser of a Kaylor win, which saw his fans break into a celebratory chorus of ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’. Rumours of battles between white supremacists and black activists had proven groundless; the guys in the ring had delivered enough action to send everyone home happy.

Kaylor Vs Christie

Christie was floored by a right hand early in round one; a one-two later in the round put Kaylor over. Mark was put floored heavily in round three, a right hand doing the damage; Kaylor roared back, stinging Christie with a right at the end of the stanza.

Kaylor gradually took over the fight, he caught Christie at the end of each subsequent round, and then finished him with right hand-left hook in round eight. Christie initially nodded to the corner, an indication that he would get up, only for his legs to fail him: the mind was willing but the body was unable. In the background, an illuminated sign read ‘Way Out’, in this bout the only way out was a KO loss; it was one of those fights.

Peace was briefly declared post-fight, they shook hands, as fighters do (James Toney-Vassily Jirov aside) and Kaylor described it as his toughest fight. To further diffuse things, Kaylor appeared in the studio after the re-run of the bout, his wife and newborn child accompanied him to reinforce the family image. Like Anthony Farnell down the line, it seemed that Kaylor was merely a committed fighter whose desire to win could be perceived as constant needle.

“No, I don’t mind people talking about how great the Kaylor fight was. I am still a little bit bitter about the fight. I shouldn’t really say this but I know there are reasons why I lost that fight. Certain elements in that fight never came out, there was so much grief going on. I was going amongst the Germans, the enemy, but that is the way things went. Mark got the spot on the night though, so best of luck to him.”

Christie, whilst acknowledging the greatness of fight itself, is still disappointed by its outcome, and the events surrounding the contest. “With me there is little things that undone me in the Kaylor fight,” explained Errol. “You will have to read my book when it comes out but there is a lot that went around with me at that time.”

“I had all those amateur fights and had been continuously training, I never took a break,” he continued. “I should have taken a break before coming into the pros. I was constantly battling and ignored what my body was saying. It was falling apart through all the action that came with boxing. I was fighting for my club and then fighting for my country, plus the lifestyle you are leading starts to play its part.

“When the Kaylor fight came about I did not just have Mark Kaylor fighting me in that ring. There were a lot of dirty things going on that people don’t realise about. No disrespect to Mark Kaylor, he beat me that night but that is the way it goes.

“No, I don’t mind people talking about how great the Kaylor fight was. I am still a little bit bitter about the fight. I shouldn’t really say this but I know there are reasons why I lost that fight. Certain elements in that fight never came out, there was so much grief going on. I was going amongst the Germans, the enemy, but that is the way things went. Mark got the spot on the night though, so best of luck to him.”

“Out in the street, in those days, you would get people calling you names, ‘Nigger’ and stuff like that. You walk into a place and you are surrounded by the enemy. I wouldn’t make friends with the enemy so I had some battles on the streets everyday back then. Then people might find out you are Errol Christie and leave you alone. I find that in today’s world people are different, but still the same. In the 1980’s people would call you to your face so you knew who your enemies were, but today we live in a sly world and you have to tread carefully.”

I asked Christie if the build-up to the fight had been mentally draining for him, especially given that the shocking loss to Reys was a fresh memory. It was claimed that the outgoing and pleasant Christie had seemed ‘unbelievably tense’ at his Thomas a Beckett training base prior to the contest, Errol, though, claims that he was in fine mental fettle.

“The mental stuff was nothing because I was mentally fit for abuse of any kind in those days,” he lamented. “You know how it went in those days: ‘You black bastard you’re not coming in here’ and ‘Get out we don’t want your sort in here’—you would get that at certain places you would go to. I would not want to go into those types of places anyway but that is how it was then. They [the few hostile voices in the crowds, and society] were the enemy for a time. They were my Germans back then.

“Out in the street, in those days, you would get people calling you names, ‘Nigger’ and stuff like that. You walk into a place and you are surrounded by the enemy. I wouldn’t make friends with the enemy so I had some battles on the streets everyday back then. Then people might find out you are Errol Christie and leave you alone.”

He continued: “I find that in today’s world people are different, but still the same. In the 1980’s people would call you to your face so you knew who your enemies were, but today we live in a sly world and you have to tread carefully. Today I know who my friends are. I am a very peaceful guy these days, but my past caught up with me early in my life.

“My life was always a battle, day in and day out. Then I came to London and could wind myself down and I stopped being so aggressive. I got out of Coventry at the right time, before I fell apart completely.

“I found that you need control in certain situations. My old amateur trainer [Tom McGarry] once took me to a boxing show in some place, Manchester or somewhere, and we were caught in the crowd coming out of a football match. We were coming out of the show and getting chips or whatever, and the football crowd started coming out. They were knocking us to the side, knocking my brother to the side. My brother is older than me and he was going to attack (them) but all of a sudden Tom told him ‘No!’, and that showed something to me. You don’t just fight at any time. You have to know when to fight.

“If we started fighting we’d have all been dead, kicked to death or anything. So that triggered something in me. On some occasions you cannot fight and you have to leave it. That situation brought that fact to my mind.”

Christie had to fight in the Kaylor contest, he was hurt early, fought on instinct for the remainder of the bout, and had to let it all hang out.

“With me, or any fighter that goes down, the first thing you want to do after being on the floor is get back up and tear back into the fight,” he said. “It is just a fighter’s thing. No fighter likes being put down. You want to get back in and rip it up. A good steady fighter will stay calm, take the count, breathe in, and try to get his senses back into his head.

“Fighters don’t like going down. We don’t practice going down. We don’t have a training drill where we practice getting knocked down. As soon as it happens you just want to jump up straightaway. It is a manly thing. You have to have a very tough attitude as a fighter.”

Christie went back to the drawing board after the Kaylor loss; some good wins followed, only for the wheels to fall off once again after a four-round four-knockdown reversal versus Charles Boston in 1986. Christie’s career ebbed away, ending at the hands of Trevor Ambrose in 1993.

“There is so much going on with the kids these days. They are left with nothing so they are left walking the streets in gangs. It is not good, kids need something to look forward to—a drive for something. Kids have all got computers. They all sit at home on their computers doing nothing. We are an unhealthy nation at the moment.”

Post-boxing, Christie posted videos of himself on Youtube; he uses these clips to discuss the pitfalls of violence and gun crime. This is Errol’s new vocation; it brings its own challenges.

“Talking to a crowd of people is quite tough to do,” he stressed. “This time is better than the times I went through though. Today’s times are much better for people. Back in the old days I was fighting in and out of the ring. If someone said something mean to me I wouldn’t leave it and say, ‘Alright, man’—I would react. I am a lot calmer now than I was in the old days. You have to live and learn.

“These young kids today, I look at them and don’t think it is as hard for them as it was for me. I like to think that we’ve moved forwards slightly. Certain elements need to be challenged in the world and it needs patience from both sides, because there are still a few problems out there.”

Errol returned to an earlier theme that we touched on in Part One, the lack of youth programmes in the UK: “I blame a lot of stuff on the Government getting rid of certain places and things. Workingmen’s clubs were great for kids, to have somewhere to go and train in boxing and Karate. It got rid of the aggression and kids used to love it. Why have they stopped doing stuff like that? Why are these sporting fields getting sold off so that people can build houses they don’t live in?” he asked.

“There is so much going on with the kids these days. They are left with nothing so they are left walking the streets in gangs. It is not good, kids need something to look forward to—a drive for something. Kids have all got computers. They all sit at home on their computers doing nothing. We are an unhealthy nation at the moment. I say bring back the seventies but without those racial elements, get them Workingmen’s clubs opened up again and get the kids doing something. Let kids turn back to sport. Sport is the best thing for building character and dedication, it will stop the kids from killing each other in the streets.”

Christie also believes that his old sport of boxing offers salvation to angry young men. He also believes that boxing provides an example of people settling geographical rivalries without shedding too much blood, just enough to entertain.

“Boxing helps you find the best boxer from your town, he fights the best kid from another town and you then fight the best kids in Europe instead of killing each other in the streets,” he claimed. “Let us give sports back to the kids and get rid of the badness in the world today.

“But I don’t like to get involved in the boxing world anymore,” he admitted. “Back in my day it was a very pretentious world and could trip into the world of celebrity and all that—it is very pretentious and two-faced.

“You very rarely see me at a boxing show or any place where there is going to be a bit of fanfare. I only like to go out to the fights where no one can see me. I like to live in darkness. I don’t like the lights coming in because you get recognised by people and get put under that torch and talked about. I’m a strange kind of guy [laughs].”

Watch Errol talk about gun crime by clicking on this link: