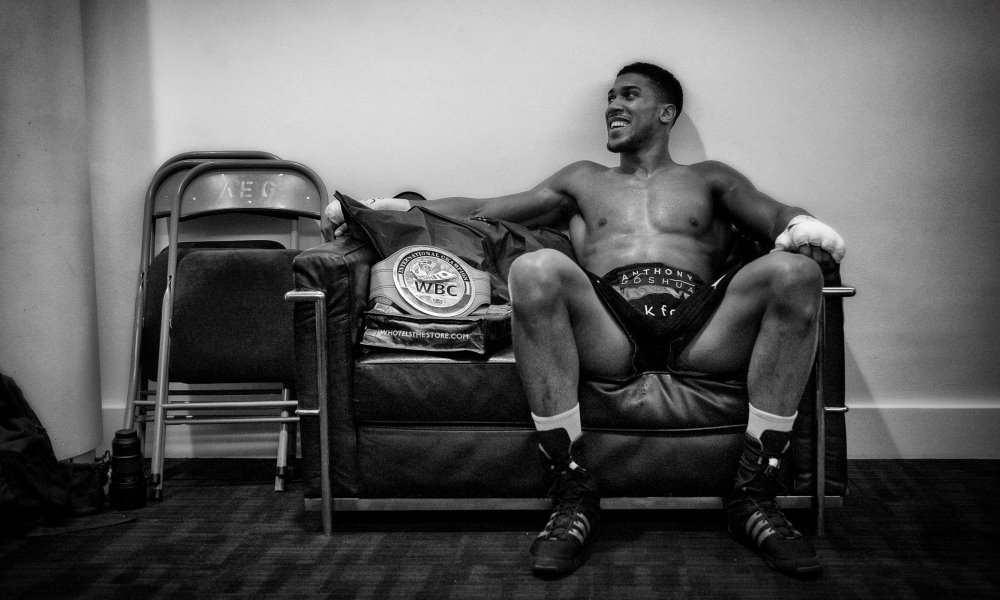

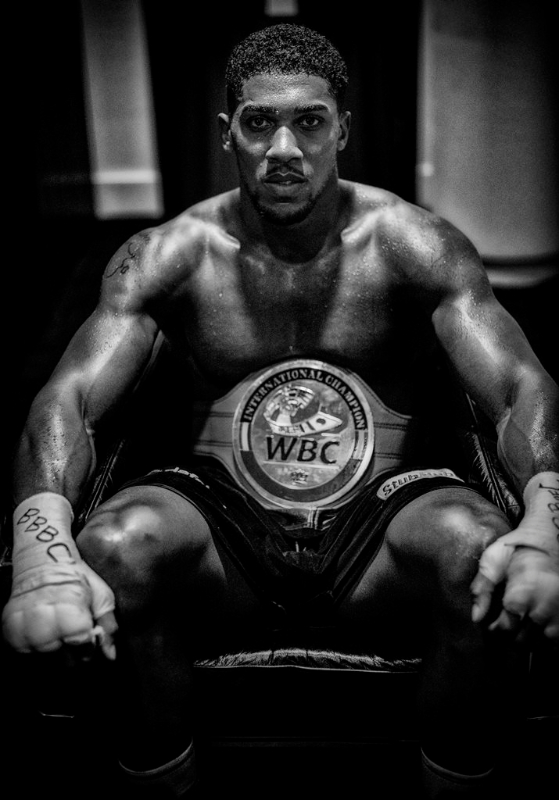

One thing that no one likes is the feeling they are being sold something worthless for a high price. Over the past few years, insistence that boxing isn’t giving fans the fights they want to see has been steadily growing, with the Floyd Mayweather – Manny Pacquiao saga still fresh in the memory. Gennady Golovkin and Saul Alvarez find themselves in a similar predicament, where neither love nor money (not even MONEY) can bring the two together, and in British circles, Anthony Joshua (and promoter Eddie Hearn) are now also in danger of incurring the public’s wrath after the IBF heavyweight champion starched Eric Molina inside 3 rounds this December in a match that failed to convince the critics of its legitimacy.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

The screams of ‘farce!’ have been quick and plentiful. Molina has been portrayed as cannon fodder, Hearn as the cash-grabbing villain in pursuit of his own interests, and Joshua as a fraud who will get found out eventually by more capable heavyweight. Such throwaway opinions are getting tiresome. Some of it I understand; occasionally the frustrations are founded in valid points, and it is worth remembering that boxing, with all its fickle marketing and back-alley negotiations, is to blame for putting everyone’s suspicions on high alert. But a lot of the commentary is needless, not to mention inaccurate, and it has finally prompted me to write Joshua’s defence on his behalf. So… here we go.

I normally see two sides to every coin, but those who claim Molina was a poor choice of opponent I wholeheartedly disagree with. When Joshua discovered boxing in 2008, Molina was winning the Texas State heavyweight title. Before Joshua was competing in the 2012 Olympics, Molina had won the WBC United States title, and by the time Joshua was knocking out the now-retired Matt Legg in his 6th professional fight, Molina had knocked out former title challenger DaVarryl Williams in his 23rd. They both knocked out Raphael Zumbano Love in 2015, a year in which Molina faced Deontay Wilder, Rodricka Ray and Tomasz Adamek (early 2016), while Joshua defeated Kevin Johnson, Gary Cornish and Dillian Whyte. The momentum was with the Brit, but Molina was in no way a lamb to the slaughter.

Out of all of those listed above, the key name is Deontay Wilder. In facing him for the WBC title, Molina was fighting a tall, muscle-bound, power punching knockout artist, and it was his job to examine Wilder further to see if he had anything else in his skill set aside from brute force. Molina gave the champion a torrid time, during which he rose from the canvas several times to hurt and confound his opponent until the 9th round, when the power of the Alabama native proved too much. For his efforts, Molina received an ovation from those in attendance and praise from the TV commentators, whilst Wilder was given a number of things to reflect on after an uninspiring win.

It doesn’t take the most active of minds to draw comparisons between Wilder then and Joshua now. The Londoner is similar size and physique, and his punch power is easily equal to, if not greater than, the American’s. Given the scarcity of opponents available at the time (most of the heavyweight division was either injured or fighting someone else when the fight was announced), Molina was one of only a handful of available men with anything close to a worthy CV. Given that he had previously asked questions of Wilder, it was reasonable to believe he might do the same of Joshua, especially as despite his world title, Joshua is far from the finished article, and needs rounds that will help him along the learning curve.

That IBF title, which Joshua won in his 16th fight, confuses matters somewhat. So, a little context; what was everyone else doing in their 16th fight? Wladimir Klitschko, the former king and Joshua’s next opponent (and former Olympic gold medallist) was knocking out Derrick Lampkins (9-3 at the time) on an undercard in Germany. It would be another 3 years and 20 fights before becoming WBO champion, at the age of 24, in 2000. Gennady Golovkin, now an unbeaten middleweight terror, was a 27-year-old prospect in 2009, knocking out Brooklyn’s Anthony Greenidge in 5 rounds. It would be another 4 fights before his first world title, and another 3 years before he first appears in America. British middleweight Nigel Benn was an angry young man of 24 years old by his 16th fight, which the ‘Dark Destroyer’ won by first round KO over Darren Hobson. Two years and 11 fights later would be his first shot at world honours. A 28-year-old Carl Froch outpointed Matthew Barney (then 21-5) for the British and Commonwealth belts, 3 years and 8 fights away from dethroning Jean Pascal. Floyd Mayweather, yet to go the full 12 rounds, was beating Gustavo Fabian Cuello over 10 in his 16th professional outing.

What does all this mean? It means that the men who become successful, long-lasting champions are built at a steady pace to become the most complete fighter they can be. The occasional freak of nature like Vasyl Lomachenko doesn’t disprove the general formula that has worked for pretty much every other world champion past and present, from Lennox Lewis to Terence Crawford. Seeing as most of those names above have an extensive amateur background (Joshua was only an amateur for 4 years), they were carrying much more experience with them into the pro ranks. Joshua, his ring experience so often cut short by his devastating power, didn’t have that privilege.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

Joshua-Molina. Was it a box office fight? No. Of course not. But the very definition of ‘Box Office’ is slowly swaying away from focusing on the headliner to being dependant on the whole event. In the Thrilla In Manila, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier delivered one of the best boxing nights the world has ever seen, yet the undercard was paltry. Sugar Ray Leonard stopped Thomas Hearns in 14 rounds in another all-time-great contest in 1981 but nothing on the undercard could hold a candle to the main attraction. Joshua-Molina was nowhere near such a standard, but the undercard more than made up for the lacklustre headliner. In total, the night included fights for two world titles, three British titles (until one was withdrawn at the last minute) and a WBA International title, and produced two Boxing News Fight Of The Year finalists, one of which won the award.

We must demand good fights, but we also have to make sure we don’t react to injustices that simply aren’t there. We all want guys like Joshua to fight the best, but we should also want him to be AT his best when he does so. It is absolutely worth seeing if he can get past men like Molina before matching him with men like Klitschko (which, as we know, has now happened). To quote Richard Schaefer, “not every football game is a Champions League final”, nor is every cricket Test match the decider of The Ashes, nor is every baseball game the World Series. We won’t get Ali-Frazier every fight, that’s just the reality of sport. Tempering our expectations, then, is tantamount to not being disappointed at each and every announcement. If you still insist on being so, it’s probably worth just waiting for the big fights and watching something else.

If you liked reading this article please share.