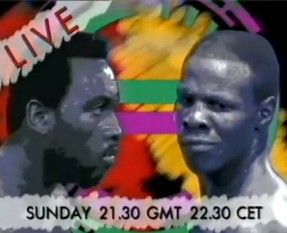

A young aspirant going up against an experienced title-holder in a fight few would have picked him to win the previous year, public opinion shifting in the build-up due to the pretender’s icy confidence and anticipation steadily building for a bout that, on paper, looks a mismatch. Words that could describe the build-up to Chris Eubank’s win over WBO middleweight titlist Nigel Benn at Birmingham’s NEC in November 1990.

Benn Vs Eubank 1 looked a shrewd financial and boxing move by the title-holder only for the underdog to prevail by ninth-round TKO. Indeed, the early pre-fight press clippings were unfavourable to Eubank only for his unyielding belief to create nagging doubts in the minds of a select view going into the first fight.

What made Benn against Eubank somewhat unique was the fact it was a world title fight here in the U.K. between two British fighters with completely different personas, styles and views on the sport. Back then, British world champions did not come around too often, and they didn’t fight each other due to this paucity of titles, so, despite being written off in some quarters as an over-hyped fight between two fighters who aren’t the best in the division (Boxing Weekly ranked them as the third and fourth best middleweights in Britain, behind Herol Graham and Michael Watson), the fight itself took off, becoming the exemplar of modern domestic “grudge matches”.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

The British are an insular bunch—it probably stems from the fact we live on an island—so it was little wonder that Benn against Eubank caught fire, set the scene for future fights and is continuously mythologised. Here’s a potted history of that first fight taken from a selection of press clippings.

In March of his title winning year, Eubank set his sights on either WBA boss Mike McCallum or Benn, assuming of course Benn could beat WBO holder Doug Dewitt in America the following month, which he duly did via an eighth-round TKO. Barry Hearn, Eubank’s promoter, told Srikumar Sen of The Times that he was confident of getting his young, unproven fighter a title shot by the year’s end—a bold claim at the time.

“We have a good relationship going with McCallum’s people,” said Hearn. “And also with Dewitt’s people, and they have said they would be prepared to come to England. Of course, we would talk to Benn and Watson if they won. If Benn fancied earning a lot of money, we could get it on.” [March 8 1990]

Either way, Eubank told Sen that he was confident of victory against any fighter in the world, arguing that only Graham or IBF holder Michael Nunn could test him. Bold talk, especially when he argued that “The media has built him (Benn) up into something he isn’t,” whilst trying to talk himself up into something that he wasn’t; he had only just elevated himself into contender status by picking up the WBC’s International title—a fringe belt that was contested by fighters ‘outside the top ten’.

Hearn had hoped to build Eubank’s status by bringing over a proven commodity, Sanderline Williams was tentatively booked in for the 25th of April, according to an article in The Independent [March 29 1990]—a move that was declared as ‘the latest step in his two-year plan to win a world title’.

Sadly, it wasn’t to be; Eubank fought Eduardo Domingo Contreras in April (W12) and seemed no closer to netting a world title shot.

Despite failing to secure the Williams fight, Eubank was thrown a lifeline as his disparaging comments about Benn’s ability had riled up “The Dark Destroyer”, who served notice that Eubank was on his radar when having a rant about the BBBoC’s decision not to sanction his match with Iran Barkley in the U.K. due to Barkley’s eye problems. The Board were also reticent when it came to rubber-stamping WBO bouts here in the U.K.

“I have had to make a heart-breaking decision to defend my world title in Las Vegas against Iran Barkley instead of fighting Chris Eubank in England,” said Benn. “The BBBC have given me nothing but trouble…When I won the title from Doug De Witt they said they did not acknowledge me as a world champion.”

The Board may have not have recognised Benn’s title just yet, but, in calling Eubank’s name, Benn was sending out a clear message: he wanted the fight, now all they had to do was nail Barkley then work out a price.

Over in Eubank Land, the Brighton-based boxer was gearing up to defend his WBC trinket against Kid Milo, although he saw the bout as beneath him. According to Nick Halling of The Independent [September 5 1990]: ‘Eubank had hoped to be fighting for a world title, but the plans of promoter Barry Hearn to match him with the WBA champion, Mike McCallum, came to nothing, leaving him with no alternative to a second defence of the title he won in March.

‘Opinion is divided on whether the Brighton boxer deserves a world title contest in the first place. His supporters cite the unbeaten record, which includes 12 stoppages, as evidence of his quality. Critics point out that he has yet to face a rated opponent, and has been made to look ordinary on more than one occasion, notably in his last fight when he was taken the distance by the slippery Argentine, Eduardo Contreras.’

Hearn, though, told Halling that Eubank was still on course to reach his destiny, saying: “Providing he comes through his next couple of bouts unscathed, Chris will have a world title fight by the end of the year.”

Milo, though, threw an aesthetic spanner into the works when picking up some rounds early before getting cut and stopped in eight rounds. Milo didn’t beat Eubank, but Jack Massarik of The Guardian was of the opinion that the fight itself was so bad it would be hard to market Eubank as a worthy title challenger, no matter how lightly regarded the WBO belt was.

‘The crouching Eubank had the measure of Milo throughout, but angered the crowd by doing no more work than was strictly necessary, preferring to pose in mid-ring and wait for Milo to rush in,’ wrote Massarik [September 6 1990].

However, a crucial moment in the “Will he, won’t he” world title saga came not in the ring, but from Ambrose Mendy, Nigel’s representative, who nailed down a price. “It would be no contest, but for a Pounds 1 million guarantee we should be interested,” he stated. “Eubank came to put himself in the shop window tonight and he did nothing to impress me whatsoever.”

In a follow up piece, Massarik took Eubank’s persona to task, arguing that: ‘The lessons of Barry Hearn’s show at Brighton on Wednesday night seem to be that it is no longer enough simply to beat your man with skill and determination; a star commodity now has to strut, swagger, taunt his opponent and generally act like the bored housewives’ favourite baddie on the wrestling circuit.’ A pretty insightful glimpse into how Eubank and, later, Naseem Hamed built up a head of steam.

People were starting to take notice within the trade, if the public was buying into it then the economic viability of a fight against Benn, and that £1,000,000 magic number, was suddenly starting to take shape.

Hearn, a former accountant, crunched the numbers following Mendy’s post-Milo claims. A day later, the promoter told Sen that he could make it work [The Times, September 7 1990], and the reporter unearthed a name for this type of Brit Vs Brit, grudge match.

He wrote: ‘The days of the “naturals’”, when you could pit one British boxer against another and fill a stadium, could be returning. The theory could be tested by Barry Hearn, the snooker and boxing promoter, in November.’

Hearn outlined just how he could manage to pull off a fight that, at the turn of the year, only one man had been calling for and make good on Mendy’s lofty purse demand. He said: “The beauty of this fight is that it is going back to the old days of massive live gates. The fight will be the promotion of Bob Arum (the American promoter) and me.”

Hearn’s claim hinged on the Birmingham NEC’s capacity to hold a large live gate that could bring in £700,000, according to The Times.

Mendy, though, was already looking for a bigger purse elsewhere. On September 12 The Guardian revealed that Benn’s handler was hoping to secure a 2.5 million pounds purse for a January meeting with Thomas “The Hit Man” Hearns. Domestic business was going to go on ice, or so it seemed.

However, Benn was never much of a poker player, while Ambrose was trying to secure a money-spinner against Hearns his charge was telling the press that Eubank was at: “[The] top of the list of people I detest.”

Benn and Mendy had recently dismissed a £500,000 offer for the fight; they were sticking to their £1,000,000 figure, which left Hearn with little time to make the numbers work for an Autumn date. Hearn, though, had confidence in his charge and was adamant that he could nail something down. When Benn didn’t get Hearns, the promoter smelled blood in the water

“I am not prepared to say what my final figure will be,” he said when speaking to the press on September 11th. “But I would not be putting the type of money on the table that I am unless I felt I was buying the keys to the chocolate factory. I think Nigel Benn will be knocked out by Chris, who I believe will go down as a legend in the middleweight division.”

A day later, he had come up with what he believed was the magic number, telling The Times that he was about to offer Benn the “highest purse ever offered to a British fighter” in order to make the fight a reality.

His fighter dissed and dismissed his potential opponent as a ‘bully’, saying: “I think he wants an excuse not to fight. Benn is capable of only knocking out a man, not teaching anybody a lesson. If he is fighting a puncher, he is the man to put your money on. He is the best puncher in the world but he is up against a skillster. He will be exposed. Class will prevail.”

Despite coming close to the number needed to get Benn into the ring, Eubank and Hearn pushed ahead with a September 22 date against Rendaldo Dos Santos (W KO 1). Decades later, Eubank’s son would fight a month before his meeting with Billy Joe Saunders, a less risky job against Omar Siala on October 25th (W TKO 2). Who says warm-up fights are risky?

“Santos is another day at the office,” was Eubank’s confident claim. “Benn is another day at the office. Just give me the fighters and I will knock them over.”

Eubank remained on course. Then Hearn did his job by coming close enough to Benn and Mendy’s figure—reports stated that Benn’s purse was around the £800,000 mark.

Furthermore, a WBO light-middleweight title fight between John David Jackson and Chris Pyatt at Leicester’s Granby Halls in October meant that the vampire had crossed the threshold, so to speak, and WBO title fights could now take place on U.K. soil. The Times reported that Benn-Eubank was on in a September 26 dispatch.

“The Benn-Eubank contest will take place and that’s all both parties are willing to say about the matter,” stated John Morris, the BBBoC’s Secretary. Modern day fans may have assumed that the news was met with dancing in the street, but, for many writers, the fight itself was a case of hype over substance.

Writing for The Guardian on the eve of the fight, John Rodda brilliantly and brutally exposed the claims that this was anything approaching the Best Vs Best. ‘Although Benn’s World Boxing Organisation title is at stake, the WBO is not recognised by the British Boxing Board of Control and not regarded seriously by anyone other than fighters, managers, promoters and TV executives,’ he argued.

‘Benn can hit very hard but has a highly suspect chin and not much boxing ability, while Eubank has not yet achieved enough for his negative, defensive style of fighting to be assessed properly…The hyperbole has undoubtedly succeeded, for the arena, which has a 12,000 capacity, is almost sold out and ITV are paying to screen the fight live; a dozen countries are also taking the broadcast in some form or other. There can be no doubt that the protagonists and their agents have been highly successful in drawing attention to the event, but whether they can match expectations is doubtful.’

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

Legendary boxing writer Ken Jones also poured scorn on Arum’s claims that Benn was the best fighter we had ever sent to the states. ‘It is nonsense to think of Benn in the same breath as Ted Kid Lewis, Jack Kid Berg, Randolph Turpin, Tommy Farr and Ken Buchanan and, in many respects, we are still looking at a relative novice,’ was his withering retort to that claim.

The pre-fight verbals between the two had started at a televised contract signing excercise—Eubank told the press that “I wouldn’t stoop so low as to say I hated him” only for Benn to let rip with “Personally, I do hate his guts”—and continued unabated day in and day out, prompting the Board to warn both to ditch the hateful words.

Despite this reticence to garland the fight with world-level written laurels and endorsements, the paying public were lapping up the all-British angle. Tickets sales remained brisk throughout. The NEC’s capacity would generate revenue of £1,100,000 according to Hearn’s revised sums—it was on course to post huge gross revenues once TV was factored into the equations.

On November 13, John Rodda of The Guardian reported that they were down to the final 2,000 tickets and they were “going fast”. A fight that seemed a distant hope at the turn of the year was now becoming a domestic monster, setting the template for the many all-British grudge fights that followed and setting one thing in stone: ‘It doesn’t matter if they’re not the best in the division, pit two British fighters against each other, stir up animosity and it will sell’.

Eubank started to turn the publicity tour into the “Chris Eubank Show”, presenting himself as a human quote machine while dismissing the more seasoned man. “Benn is chinny,” he said when speaking at a press conference on November 12 [The Times, November 13 1990].

“It will last no more than seven rounds. All those who have put their money on Benn will lose it. I’m going to knock him out him in three rounds, certainly before the seventh and it will happen.”

He wasn’t done, either: “He was a coward when he fought Michael Watson, turning away from punches. Whether there is any cowardice left remains to be seen on the night…He’s just an ignorant puncher. I’m an intelligent boxer and a competent boxer will always beat an ignorant puncher. He’s not in my class.”

Although these was scepticism over his chances within the press, a few within the trade were starting to lean towards the eccentric outsider. Step forward Barry “Nostradamus” McGuigan and Jim McDonnell.

“If the fight goes over six rounds Eubank will win inside the distance,” was McGuigan’s prediction. “If anyone wins early it will be Eubank,” added McDonnell. “If it’s a long fight it will be a question of who wants to win most.”

Herol Graham also had faith in the new kid on the block, he told The Observer’s Alan Hubbard that Eubank had floored him in sparring with: “[A] very good shot. If he catches Benn like that, Nigel will go.” Ironically, Graham fought Julian Jackson for the vacant WBC title shortly after. The Sheffield boxer earned around £60,000 for that fight. Eubank was said to be on £100,000 for his fight with Benn. Had he won, there were plans to match Benn against Nunn in a transatlantic money-spinner.

The Eubank hype express was picking up passengers en route to fight night, but he didn’t stand a chance, or did he? We all know what happened, Eubank stopped Benn to kick start a British round-robin that, although strictly a local concern, is still revered within the trade and by fight fans. When you hear the words “These two really don’t get along!” remember who set the template for these all-British, inward looking affairs that the general public laps up.