An in-depth look at the heavyweight division’s Golden Age by Ian Probert, this article was penned in 2013, the year Ken Norton died, and prior to Muhammad Ali’s death last year.

It’s a balmy sunny day in August 1970 and former undisputed heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali is sitting in the passenger seat of a gold coloured Cadillac convertible. The grill and the hood are smashed in, testament to the ineptitude, recklessness and disregard for money of the vehicle’s driver, current heavyweight champion and sometime nightclub singer Joe Frazier. ‘I make like thirty thousand in less than about four five weeks just singing,’ boasts Frazier, as he drives unsteadily through the streets of New York.

‘Awww, you ain’t got that kind of money, man,’ says Ali, his eyes suddenly widening as the other man opens up his wallet and displays its contents. ‘Wow, you carry that much dough in your wallet?’

Frazier smiles. ‘Four, five hundred,’ he says. ‘Need some?’

‘How about a hundred?’ asks Ali. ‘I may stay overnight.’

‘Yeah, okay.’

‘Pay you next week,’ he says, pocketing the hundred-dollar bill that Frazier has just passed to him and staring into space as if in a daze. ‘I owe Joe Frazier a hundred dollars. Never thought the day would come when I’d owe Joe Frazier one hundred dollars…’

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

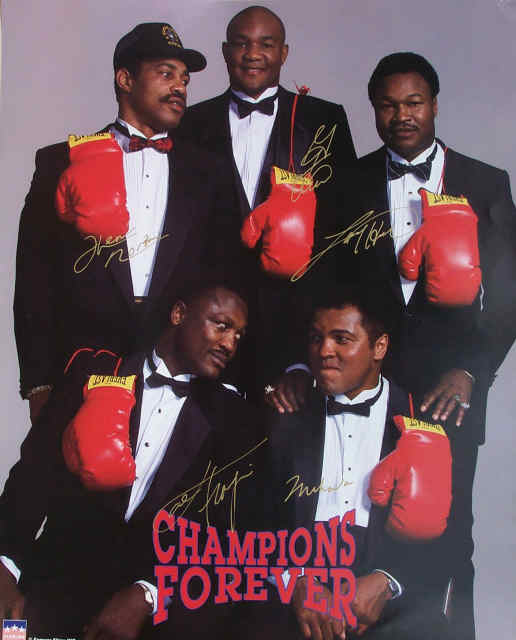

In September 2013 former WBC heavyweight champion Ken Norton died after a long battle with illness. Norton was an unusual fighter: not so much because of an awkward style that frequently gave technically superior boxers palpitations, but more to do with the fact that he remains the only heavyweight champion of the modern era never to win or defend his title in the ring. It’s an unenviable record and hints perhaps of good fortune or even corruption. But there was more to Kenny Norton than a Trivial Pursuit question. For Norton was an illustrious member of an elite quintet of fighters that lit up boxing in the 1970s in the same way that Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns and ’Sugar’ Ray Leonard illuminated the sport in the 1980s.

I’m talking of course about Norton’s distinguished heavyweight contemporaries Muhammad Ali, George Foreman, Joe Frazier and Larry Holmes. In all these five giants of the ring were involved in 12 separate contests. Holmes fought in two of these, Foreman in four, Norton and Frazier in five, and Ali in eight. It was a rivalry that began with Ali in 1971 and ended with Ali in 1980. And during that nine-year period a worldwide audience of boxing and non-boxing fans were thrilled to be able to bear witness to a series of battles that scaled hitherto unheard of heights of drama and excitement.

Round One – Joe Frazier WPTS 15 Muhammad Ali, 08/03/1971

It was billed as the ‘Fight Of The Century’ and as if to give credence to this exotic claim Frank Sinatra was employed by Life magazine as a slightly starstruck ringside photographer. It took place in Madison Square Gardens and was the first and only time that two undefeated world heavyweight champions were to meet in the ring. It was a battle of contrasts. In one corner was reigning WBC and WBA heavyweight champion Joe Frazier. Born in South Carolina in 1944 Frazier looked every inch what a fighter was supposed to look like. With massive shoulders honed from chopping wood and a face that looked like it had come prepackaged with lumps and bruises in anticipation of it’s owner’s chosen career, Frazier presented an intimidating spectacle. In the other corner was Muhammad Ali: handsome, unmarked, brash, arrogant, the dictionary definition of an Adonis. The very antithesis of what a boxer was supposed to be.

The background to the fight is well known but still worth repeating: Ali, Olympic Gold medalist in the light-heavyweight division in 1960 was then the most famous boxer on planet earth; later he was to become arguably her most famous person. After a rapid rise to prominence characterised by impossibly fast movement and reflexes in the the ring and an improbably fast mouth out of it, Ali – then known as Cassius Clay – had claimed the heavyweight crown in 1964 with a stoppage win over the brutish Sonny Liston. Immediately after the fight Ali had abandoned his given name and announced his conversion to Islam. This move mystified and frightened much of middle America. Three years later when Ali refused to to be drafted into the army he was stripped of his titles.

In retrospect, this was a terrible loss to the sport of boxing: Ali, who had proven himself peerless in making ten exquisite defences of his title, was at the height of his powers. While others sought to fill the gap left by his absence, Ali’s energies and rapidly dwindling finances were devoted instead to a lengthy legal battle to avoid incarceration.

But Ali’s loss was to be Joe Frazier’s gain. An Olympic gold medalist himself at heavyweight in 1964 Frazier had been on a collision course with Ali since turning pro. Frazier’s most powerful weapon was a juddering left hook, which saw him rattle through the opposition to claim Ali’s vacant title in 1968. And while it would certainly have been interesting to have seen what what would have happened if the pair had met with Ali as Champion and Frazier challenger, the closest we ever got to it was in their 1971 meeting.

Three years out of boxing, Ali had wisely attempted to rid himself of the ring rust with a couple of largely unconvincing tune-up fights. The ex-champion was the favourite but Frazier was buoyed by the confidence of his conviction that he was actually a better fighter than his rival. And in 15 workmanlike rounds that never quite lived up to the fight’s billing Frazier proved that he had it within him to slow down Ali’s movement with body shots that resembled Stallone hitting a cattle carcass, hurting him in round 11 and finally felling Ali with that vaunted left hook in the final round. Ali had been down before, memorably back in 1963 in England by Henry Cooper, but in managing to regain his feet and complete the remainder of the round Ali had demonstrated that he had bravery enough to match the speed that at 29 was already a rapidly diminishing attribute. It was this bravery which would ultimately cost Ali more than any title.

Round two – George Foreman WTKO2 Joe Frazier 22/01/73

Enter George Foreman.

Born in Texas in 1949, Foreman was the third of the quintet to win the Olympic Gold medal, this time in Mexico 1968. But whereas Joe Frazier at 5’10” was a relatively small heavyweight, Foreman at almost 6’ 4” and weighing 218 pounds was a giant with a knockout punch to match. The jovial punching preacher from the grill commercials that we all know and snigger at today was definitely a thing of the future. In those days Foreman was a devastating puncher full of brooding menace. Since turning pro in 1969 Foreman had knocked out 34 out of 37. It has often been said that Foreman was the Sonny Liston of his day but he was was far more frightening. His movement may have been limited, his boxing skills possibly even more so but his punch made up for any such weaknesses. It truly was the great leveller, as a certain Michael Moorer was to find out 21 years later.

Frazier and Foreman met at the National Stadium in Jamaica with the champion being the bookies’ favourite. In the event the fight proved to be a complete mismatch. The challenger simply walking through whatever Frazier had to offer. Within two minutes Frazier was down from a clubbing uppercut. By the end of the round the champion had been on the canvas three times. Frazier hit the canvas twice more in round two, the final punch literally lifting the Philadelphian off his feet. It was a forbidding performance by the 24-year-old Foreman that redrew the heavyweight map.

Round three – Ken Norton WPTS12 Muhammad Ali 31/03/1973

In retrospect the decision to match Muhammad Ali with handsome former marine Ken Norton was at the very least risky. Norton, who came into the fight with a record of 29 wins and one loss was hardly the stuff of journeymen. Even so, Muhammad Ali, on a run of ten straight wins since the Frazier loss was supremely confident, telling onlookers that Norton was an ‘amateur’.

Unfortunately for the ex-champion the ‘Amateur’ managed to throw a punch at a certain point in the fight that fractured Ali’s Jaw. ‘I was taking out the mouthpiece and there was more and more blood on it,’ recalled Ali. ‘My bucket with the water and ice in it became red…’ Ali claimed that the injury occurred in the early rounds but Norton maintained that it happened in the final round.

Whatever the truth, Ali managed to remain competitive while trying to protect his injury. The fact that he lost a split decision nursing such a profound disability is further evidence of his reckless bravery. For Ali, however, the loss was a disaster. If he was ever to fight new heavyweight king George Foreman for the title he now had two men to beat: Norton and leading contender Joe Frazier.

Round four – Muhammad Ali WPTS12 Ken Norton 10/09/73

Muhammad Ali waited six months for his jaw to heal before once more stepping into the ring with the fighting marine. The pair met in California where Ali struggled to achieve a points decision over his conqueror. Norton, it was becoming obvious, was Ali’s bogey-man. His herky-jerky style and habit of throwing the jab from the waist were qualities that Ali could never quite master. There could be no excuses this time: Norton had proven that he had what it took to take to stretch Muhammad Ali to the limit.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

Round five – Muhammad Ali WPTS 12 Joe Frazier 28/01/74

Although he would never admit it, Joe Frazier had obviously gotten under Muhammad Ali’s skin. Gone were the days when the two rivals could happily sit together in Frazier’s car; Frazier was hard-pressed to even give ‘The Greatest’ the time of day, let alone lend him money. This was because Ali had unleashed the full weight of the cruelest aspect of his nature on the hapless Frazier. Frazier was not ugly, nor was he stupid, nor was he an ‘Uncle Tom’. But such was the force of Ali’s personality that when he called his opponent those things during the build up to their second meeting people tended to get taken in by his words. Ali later claimed sheepishly that he was only trying to sell the fight but he had to have been aware that this was a fight that sold itself.

The pair met again at Madison Square Gardens but this time the result was different. Another largely uneventful contest saw Ali claim a points decision. The crowd were somewhat underwhelmed, this was not even the fight of the month let alone the fight of the century. They had expected a little more drama — they would get it when the pair met for the third time.

Round six – George Foreman TKO2 Ken Norton 26/03/74

Norton’s unlikely reward for losing to Muhammad Ali was a shot at Foreman’s heavyweight title. The pair met in Venezuela. Surely Norton who had pushed Ali so hard over 24 rounds, reasoned critics, had what to took to push Foreman a little harder than Frazier had? And indeed he did. In fact, Norton managed to stay on his feet for the whole of a forgettable first round. However early in the second, a brain scrambling left hook deposited the challenger on the canvas. After climbing groggily to his feet another attack from the taller man had Norton seeing stars. Was there anybody who could stop George Foreman?

Round seven – Muhammad Ali KO8 George Foreman 30/10/74

‘Foreman turned his back. In the thirty seconds before the fight began, he grasped the ropes in his corner and bent over from the waist so that his big and powerful buttocks were presented to Ali. He flexed in this position so long it took on a kind of derision as though to declare: ‘My farts to you.’’

—Normal Mailer, The Fight, 1975.

Muhammad Ali’s finest hour? Possibly. Boxing’s greatest spectacle? Most probably. Ali was thirty-two-years-of-age and could no longer dance. That is to say Ali wasn’t aware that he could no longer dance until he got to the end of a first round in which he had been relentlessly pursued by his 26-year-old opponent. It was at this defining moment that Ali was made aware of the limitations of age and chose to improvise. In the steaming jungle of Kinshasa, Zaire, before a worldwide audience of millions, Muhammad Ali reinvented himself. Choosing to lay back on the ropes and invite the giant behemoth Foreman to aim punches at him, Ali picked away at his opponent as if he was unravelling a particularly stubborn and annoying thread.

At ringside, onlookers were in tears, genuinely believing that George Foreman was about to kill the ex-champion. And on many occasions it appeared that might just be the case: Ali apparently wilting under the constant shower of bombs that fell in his direction. But the monumental effort took its toll on Foreman. By the seventh round he was looking desperately for a second wind. It never came. Foreman seemed almost grateful to be gazing sleepily up at the ring lights as a succession of quick-fire punches felled the giant fighter.

Many of those present at this amazing spectacle failed to realise in all the excitement that they had just witnessed a kind of magic. Boxing’s greatest conjurer had undertaken boxing’s greatest conjuring trick. For a moment boxing ceased to be just a sport.

Round Eight – Muhammad Ali TKO 14 Joe Frazier 10/01/75

After the majesty of Zaire everything else just had to be an anti-climax. Surely? So it appeared when Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier stepped into a Manila ring for their monumental and now legendary rubber match. After the Foreman fight Ali had been showing signs of age, only managing to defeat Ron Lyle with a desperately late rally and waltzing to a unanimous decision over Joe Bugner. Even so, Frazier was deemed to be easy meat. Not the same fighter after his mauling by Foreman. Well past his sell-by date.

Watch the video and you’ll see that most of this was true. What becomes apparent, however, is that the decline of the two fighters, the erosion of their skills, had more or less matched one another for pace. The core of what remained however, was pride and determination in such abundance that it very nearly killed both men.

There was nothing scientific about this third encounter. Both men choosing to trade blows until there were no more blows to trade. If we saw such an unremittingly brutal spectacle in a movie we would be shaking our heads in mocking skepticism. During the build-up to the contest Ali had humiliatingly dubbed Frazier ‘The Gorilla’; Frazier’s son had even been bullied in the playground. Frazier found extra reserves of energy in an effort to force those insults back down Ali’s throat. And he very nearly did.

By the climax of an epic fourteenth round both men were ready to fall. In actual fact, in the end it came down to an attritional battle of trainers. Would Angelo Dundee or Eddie Futch see sense and draw a close to the carnage? History records that it was Futch who made that fateful decision, seconds before Ali was apparently ready to pull himself out. Whatever the case the fight effectively signalled the end of both mens’ careers. They had literally punched the life force out of each other. There was very little left.

Round Nine – George Foreman TKO5 Joe Frazier 15/06/76

There may have been very little left but when it came to gameness Joe Frazier could not be faulted. A mere five months after his titanic struggle in Manila Frazier was back in the ring with the only other man to beat him. For his part, the fragile psyche of George Foreman was in the rebuilding stage. After that devastating loss to Ali, Foreman was involved in a crazy up and downer with dangerous slugger Ron Lyle in Ring Magazine’s Fight Of The Year (if you’ve never seen it, folks, YouTube it right now!). He had also travelled to Montreal, where he fought five men in the same night in an exhibition. (Not at the same time, it has to be said).

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

In their marginally more competitive rematch Frazier, sporting a shaven head and chin, managed to last until round five before succumbing to Foreman’s relentless pressure. After the fight Frazier retired, leaving Foreman to continue his quest for a rematch with Ali. This was never to happen. Four fights later George Foreman was beaten by Jimmy Young and he himself retired after seeing visions in the dressing room afterwards. Nobody in their wildest dreams would have anticipated that 17 years later Foreman would reclaim the linear heavyweight crown.

Round ten – Muhammad Ali WPTS15 Ken Norton 28/09/76

Having spent 39 rounds in the company of Ken Norton, Muhammad Ali could have been forgiven for vowing never to get into the ring with his bête noir ever again. If any more evidence were needed that Ali was incapable of finding a solution to Norton it was provided in their third encounter, this time at Yankee Stadium. Again the fight was by no means a classic. There were no broken jaws and in fact most neutrals had Norton winning by a comfortable margin. Not so the judges, who always favoured Ali in the way that modern time-keepers favoured Fergie. Indeed, retrospective punch stats reveal that Norton connected with 286 total punches to Ali’s 199.

Round eleven – Larry Holmes WPTS15 Ken Norton 09/06/78

After Muhammad Ali unexpectedly surrendered his crown to seven-fight novice Leon Spinks (yet another Olympic heavyweight champion), Norton was named leading contender. But instead of fighting Norton, Spinks opted for a toothless rematch with Ali and thus the WBC title was awarded to Norton without a punch ever being thrown. Punches were duly thrown, however, in Norton’s first defence of his title. Larry Holmes, the last of our quartet of kings, had been one of Ali’s sparring partners and had learned well from his employer.

Born in 1949 in Easton, Pennsylvania, Holmes’ development as a fighter had been protracted and without fanfare. Often fighting on the undercards of Ali fights, it was now Holmes’ turn to carry the torch. Just as Ali had done, the cultured ‘Easton Assassin’ struggled to accommodate Norton’s unusual style. And it took an incredible fifteenth round for him to win on the tightest of split decisions. The Larry Holmes era had begun.

Round twelve – Larry Holmes WTKO10 Muhammad Ali 02/10/80

It is one of boxing’s grand traditions that in order to achieve true succession the young lion must first annihilate the memory of his predecessor. So it was that an aged Muhammad Ali returned to the ring after a two-year layoff in order to officially pass the baton to his former protégé. A lot of people wondered what a seventies icon such as Ali was doing in the eighties. But for his part the great conjurer almost convinced onlookers that he had one final miracle left in the gas tank. Ali was thirty-eight-years-of-age but externally looked almost as he had done way back in the first Liston fight. Internally, however, Ali was a sick man. Already suffering from the early onset of Parkinson’s syndrome, taking medication for a thyroid disorder, and his slim torso not honed by dedicated training but by diet pills, Ali was not even a shadow of the shadow of the fighter he once was.

As always Ali took his beating like a man; with Holmes visibly concerned for the well-being of his former employer as he aimed reluctant blows at his immobile foe. Those that were able to watch the slaughter through cupped hands noted that the fight was finally stopped in round 10. In truth, it should have been halted several weeks before the opening bell.

The death of Ken Norton leaves only three of the quintet of kings surviving. Joe Frazier died in 2011, never forgiving or forgetting the taunts that had been aimed at him by his greatest opponent. Larry Holmes and George Foreman both made comebacks that lasted well into their forties. Holmes tried three more times more to regain a version of the world title that he had lost to Michael Spinks, losing on points to Evander Holyfield and Oliver McCall and getting knocked out for the only time in his career by Mike Tyson. Foreman was also decisioned by Holyfield before regaining his title with that astonishing knockout of Michael Moorer in 1994.

Muhammad Ali was the only one of the quintet to fight all four rivals. And he bears the wounds of those fights to this day in the most awful way imaginable. The man who was once boxing’s most splendid exponent and finest advertisement is now a shambling wreck, a grim warning for anybody who ever wishes to lace up the gloves.

Ian Probert

https://ianprobertbooks.wordpress.com

Twitter: @truth42

Visit http://ianprobert.com/ for details of Dangerous, Ian’s latest boxing book. you can also access his work on fiction, including his critically acclaimed book Johnny Nothing, by going to his Amazon page via this link.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]