A landmark signing for Frank Warren and BT Sport, Josh Warrington talks to Danny Flexen about his next fight and why he is the right man at the right time

A STATEMENT of intent. There are times, in any industry, when a talent acquisition represents more than the sum of its parts. The deal in question may be indicative of a wider power shift, and serves to put the business in which the protagonist operates – and, most importantly, their closest rivals – on notice. When Manchester City boldly signed Carlos Tevez from under the noses of neighbours United in July 2009, the sheer audacity involved told the football community that the club’s wealthy owner Sheikh Mansour, presiding over his first full summer transfer window, was a hugely ambitious man, for whom nothing was off limits. United had been crowned champions in each of the previous three seasons, the later two boasting an influential Tevez orchestrating the forward play. Although City would not win their first Premiership title for another three years, as a genuine contender they had arrived.

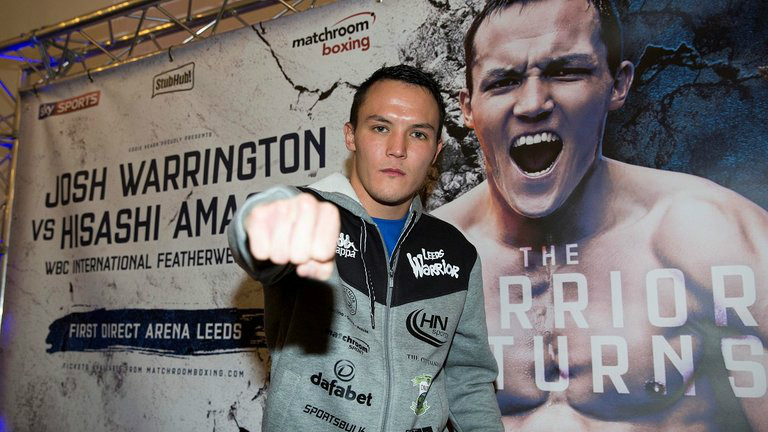

Josh Warrington, the ostensibly unassuming Leeds featherweight who nonetheless sells thousands of tickets for his fights, has become boxing’s unlikely Tevez. The Argentine attacker had shone in two campaigns on loan at United, just as Warrington had strode to the verge of a world title shot while handled by Matchroom, the dominant promotional entity aligned with Sky TV in what at times felt akin to a UK monopoly. But with Warrington’s contract elapsing in November just days before Frank Warren’s landmark announcement regarding his link-up with media behemoth, BT, the stage was set and the leading man all but cast. Warren has recently spoken of his greater ability, under the BT umbrella, to stage the monumental showdowns, facilitated by their almost unrivalled financial muscle; of at least equivalent value is the attractive proposition he can now present to unattached fighters, one that incorporates dedicated combat channel, BoxNation. A 27-year-old with his best form most likely ahead of him, Warrington became one of the first high-level boxers in recent times who, having spent a lengthy and lucrative period with Matchroom, then departed, albeit by mutual consent, and joined Warren. His impressive stoppage win over Patrick Hyland in July would be his last as a Sky fighter; the BT revolution had its prince.

“They were trying make a bit of a statement,” the naturally humble Warrington concedes. A deep, almost growling Yorkshire brogue belies the baby face and friendly nature. “I’m not gonna blow smoke up me own backside, it’s an honour they consider me a big fighter. The opportunity to be the flagship-bearer for the stable, the time and effort that would go into me, influenced my decision. “Maybe it’s the start of a load of big fighters signing with them. Fighters can be sceptical, they don’t like change. When Eddie first came on the scene, as soon as one went [and signed with him], everyone went; now they’ve got an option.

“Sky are relying a lot more on PPV cards, there’s no Ringside [magazine show] anymore and I wonder which way they’re going. I’ve read about how much money BT have ploughed into football and I think they’ll make a real go of it. It’s great to be at the start of that, there’s real enthusiasm, BT are a breath of fresh air.”

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]

The relationship between Warrington and Matchroom was, for the most part, mutually beneficial – that rarest of things in a sport that is, by its very nature, inherently selfish. Eddie Hearn’s team, alongside broadcast partner Sky, provided the exposure and support that helped Warrington to build his profile and progress through the world rankings, while Josh fulfilled his end of the bargain via self-promotion, selling tickets, and, of course, winning the fights themselves in generally entertaining fashion. If this was a marriage of convenience, then it was very convenient indeed, for both parties.

“Sky are relying a lot more on PPV cards, there’s no Ringside [magazine show] anymore and I wonder which way they’re going. I’ve read about how much money BT have ploughed into football and I think they’ll make a real go of it. It’s great to be at the start of that, there’s real enthusiasm, BT are a breath of fresh air” —Josh Warrington

Gradually, however, prevailing trends eroded a previously successful arrangement. Operating as the market leader brings its own challenges, not least keeping everyone in their organisation happy, and, with the promoter’s stable growing over-populated, some of their loyal soldiers had to accept they would be competing less often. Allied to that, ever since pay-per-view boxing made its polarising return in 2013, the Box Office element of the Matchroom-Sky portfolio has grown ever-more relevant to the bottom line, while generating revenue from ticket sales has become arguably less of a priority. Warrington fought three times per annum from 2012-2015 inclusive, but only twice last year. He participated in a total of nine Matchroom shows – six at a Leeds Arena the local hero has made his fortress, with attendances recently going over the 10,000 mark – but never appeared on a PPV. Warrington may feel, justifiably, that he has contributed to elevating the company to their current advantageous position, yet has found himself unable to reap the fruits of that labour.

“I enjoyed my time with Matchroom and Eddie and I’m only 26, time’s on my side,” Warrington reflects, characteristically taking care not to seem overly harsh or ungrateful. “What I was doing was a lot of hard graft, selling shows, I do a couple of thousand tickets [individually], and I wanna get a bit more praise and reward for that. There was a bit of frustration, there was no [fight] date, talks of a world title shot against Lee Selby every year and that didn’t happen. The Patrick Hyland fight weren’t gonna happen, they was gonna go to Hull, then Doncaster, then it was, ‘Josh, can you go to Leeds?’ I thought I’d just have a steady one, but then it was, ‘We need a headline show’. My contract was coming to an end, dad [and trainer, Sean O’Hagan] and [manager] Steve [Wood] said I really needed to consider other options. Fighters wanna be out on numerous occasions, that’s why you saw so many stacked on that card in July because they’d not been out in a while, all top names on that show because they needed an outing. You need to be out there to keep your momentum going, you can spar thousands of rounds in the gym but it’s not the same as fighting under those lights.

“I think there was more enthusiasm from Frank than everyone else. We were enthusiastic that they were gonna sign the contract with BT and wanted to work with us.”

Unlike Tevez, this isn’t a superstar making the move, it’s the move theoretically making a superstar. The spoils Warrington expects to gain from his new allegiance are abundantly clear but, broader implications aside, how can Warren and BT benefit directly from their new signing? He is unbeaten in 24 contests (all wins), holds the WBC International belt and resides in their top four and that of the IBF. Along with Tyrone Nurse, another recent BT convert, he can virtually guarantee big money from Leeds Arena cards and the huge, passionate crowds that also enhance the televisual presentation of any sports event. His appeal has frequently been compared to that of Ricky Hatton, one of Warren’s biggest ever draws, and if Warrington can successfully transcend the hardcore fanbase he has built and inspire similar devotion from the armchair viewer, BT’s star will rise inexorably alongside his own.

“Some people kinda think this happened overnight, but it’s far from it,” he states, a little defensively, regarding his undeniable popularity. “I’ve been a pro since 2009, and it takes a lot of time and effort, a lot of f***ing stress. I came through under the radar, fighting on small-hall shows, made my pro debut at 18 and had 70 school pals come down. As a young prospect with no massive amateur background, I had to do it the hard way, going on shows all over the country. If you’re a young prospect with no Olympic medal or sponsors coming out you’re a***hole, it’s difficult.

“I tended to go out and spend time in pubs with my friends, trying to get me name out there whenever possible,” he explains, his tone softening with the sepia-tinged nostalgia of recalling tough but rewarding days gone by. “I always thought about how much I love Leeds and how much I wanna put the city on the map, and I’d try to get that across. For a while, it didn’t really happen, but I kept thinking it’d come.

“The breakthrough was when I won the Commonwealth on Sky against Samir [Mouniemne, in the his opponent’s native Hull], people really started to take notice, and at the same time I started doing stuff with Leeds United, which was a dream come true. That were [the result of] years and years of putting posters up in takeaway shops, in my spare time when I were working as a dental technician and studying to qualify too.”

“I’ve been a pro since 2009, and it takes a lot of time and effort, a lot of f***ing stress. I came through under the radar, fighting on small-hall shows, made my pro debut at 18 and had 70 school pals come down. As a young prospect with no massive amateur background, I had to do it the hard way, going on shows all over the country. If you’re a young prospect with no Olympic medal or sponsors coming out you’re a***hole, it’s difficult” —Josh Warrington

Josh did ultimately attain his qualification, though gradually reduced his hours and eventually resigned as the demands on his time proliferated and more sponsors came on board. A full-time pro for several years, Warrington now embarks on the most crucial stage of his career, one that, while transmitted by a new TV station (for him), begins in a familiar setting. In his next fight, Warrington meets former IBF king and regular visitor to these shores, Kiko Martinez, on May 13 at his second, rather palatial home and could easily be one convincing victory away from that coveted world title shot.

“Originally, when they announced Marco McCullough for my next fight, I were a bit shocked to be honest,” Warrington admits regarding the bout initially mooted for his BT/Warren debut. “I know I’d had a little bit of time out the ring, but I should have got more credit for beating [Hisashi] Amagasa – he was in the top three of all the governing bodies a few years ago – then boxing Hyland who’d only lost to world champions; we had a lot of good momentum. When I come back, especially with a new promoter and TV channel, I wanna come back with a big fight; no disrespect to Marco, he’s a good fighter, but we felt we were beyond that level, and I wanted a fight that would definitely make me get up for it.

“We asked for a big name, and when they came back with Martinez, I were like, ‘That’ll do.’ He’s been over here, fought [Carl] Frampton twice, [Scott] Quigg, even as far back as Rendall Munroe. There’s everything really, he’s a former world champion, tough as they come, he can punch – he’s had more knockouts than I’ve had fights – he makes an entertaining fight, and it’s good to get back in there with someone like that.

“I just want to get a shot. The last couple of years, I’ve beaten [Joel] Brunker, Amagasa, Hyland, now someone like Martinez. I’m really eager to get a shot at someone like [IBF champion and longtime rival] Lee Selby but if they came up with any other champion I’d be happy. I’m getting to the stage where I want to take a shot at the next level and see how it goes, I feel like I’m really starting to hit my peak. Once I beat someone like Martinez, I’m already highly ranked by governing bodies, where else do you go? I don’t want it to be like Jamie Moore and I never get that shot, it’s all about timing in this game, things can change very quickly.”

Moore was also managed by Manchester stalwart Steve Wood, so perhaps sharing a mentor has instilled in Josh a heightened awareness of a boxer’s limited window of opportunity, and, among myriad other factors, compelled Warrington to hitch his wagon to a fast-rising enterprise for whom he would be a focal point. More star names will inevitably join him in the Warren/BT fold, but at present no Tyson Fury, Anthony Joshua or Kell Brook stands in his way; for this boxing insurgency, the proud Yorkshireman represents both the present and the future. Heavy is the head that wears the crown, but the prince of the revolution wants only to be a king.

[sam id=”1″ codes=”true”]