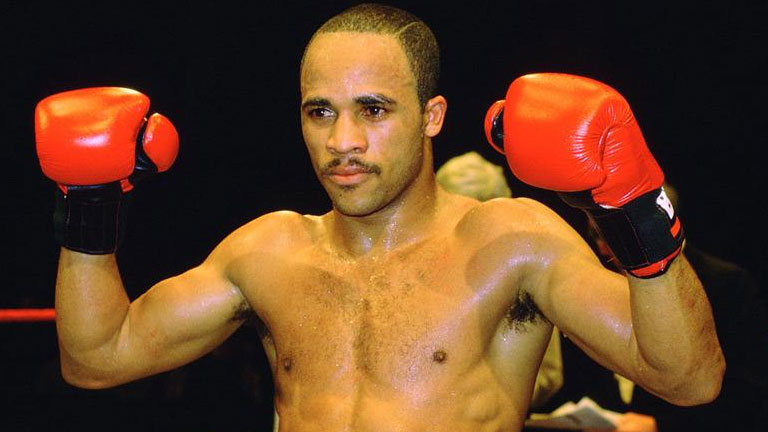

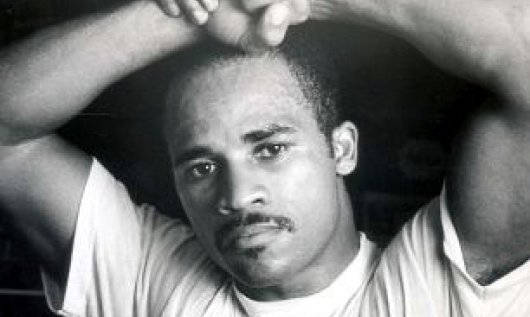

Lloyd Honeyghan must have thought that he had seen it all going into his November 27 1985 contest against Sylvester Mittee. ‘The Ragamuffin Man’ had compiled a perfect 25-0 slate and was the EBU welterweight champion. There had been few surprises in Lloyd’s career thus far but British and Commonwealth boss Mittee managed to throw the 25-year-old a curveball ahead of their clash by presenting Lloyd with a bunch of flowers.

Mittee was riffing on the recent street scuffle between middleweights Mark Kaylor and Errol Christie. The St. Lucia-born boxer warned Honeyghan to steer clear of the thorns yet it was Mittee who was cut to shreds come fight night. Referee John Coyle stopped the bout at 1:39 of round eight on the advice of the ringside physician. Sylvester had been floored twice and despite a few bright spots was well beaten.

Lloyd had successfully annexed Mittee’s British and Commonwealth titles; he was now on the brink of breaking new ground as a pro. Flora and fauna from Sylvester and now the possibility of world title garlands as news filtered through that both Don Curry and Milton McCrory were struggling to boil down to the 147lb weight limit for their December 6 unification fight. Whispers suggested that should both men would miss the weight the fight itself would still take place minus the WBC, WBA and IBF titles.

Curry’s manager, Dave Gorman, had previously insisted that his man was making the trip down to welterweight for the final time, leaving the winner of Honeyghan-Mittee free to fight for the vacant belts. Both men eventually made weight and Curry prevailed via a one-sided, two-round icing of his world title rival. However, the lure of defending the unified titles proved too much for the ‘Lone City Cobra’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7GfCVvvlBX0

Don was riding high in the P4P rankings. Many US critics had him ahead of Marvin Hagler, no small feat when you consider that Marvin had the scalps of Roberto Duran and Thomas Hearns on his slate. Honeyghan was rated highly in Europe yet his single-minded approach had turned a few people off him. Especially when he did the unthinkable and dispensed with the services of trainer Terry Lawless, claiming that, “Everywhere I went with Terry I got the feeling I was only there because Frank [Bruno] was. I wanted individual attention because I knew I would be a champion”, when announcing the split.

Lawless was hugely respected. Honeyghan was perceived as headstrong, he did not care; the undefeated fighter employed Bobby Neill, a former British featherweight titlist, as his coach and moved on. The rest is history, Lloyd went over to Atlantic City in September 1986 and ripped the WBC, WBA and IBF titles from the undefeated pound-for-pound kingpin at a time when British fighters tended to fail on foreign soil.

Lloyd joined Hagler as the sport’s sole undisputed ruler after forcing Curry to withdraw after six rounds due to a cut to his left eye—the wound required twenty stitches. Lloyd gave his opponent a broken nose to boot, doing enough damage to prompt the ringside doctors, Paul Williams and Frank Doggett, to pull Curry from the firing line. Hey presto, Lloyd was now an international name and, in his mind, worthy of a spot in the record books.

“I just walked along the boardwalk and someone recognised me,” said Lloyd after his title win (The Guardian, September 29 1986). “They said they were glad I’d beaten Curry because he was arrogant. I called my mum and dad in England and they said the papers there didn’t give me a chance either, but they believed in me. The papers’ll have to eat their words. I bet Donald Curry discovers now who his real friends are. But I’m not going to let it change me. I’ll keep the friends I’ve always had.”

Honeyghan, never shy when assessing his own ability, had the world at his feet yet he had been quick to remind the assembled press that he was also the ruler of Britain, Europe and the Commonwealth. He said: “That makes six championships in all. That should put me in the Guinness Book of Records.”

Despite the nature of the win over Curry there was a certain amount of scepticism in the U.S. Curry had battled the scales in previous title contests, (in)famously resorting to chewing gum to generate saliva when drying down to 147 for a WBA and IBF defence against Colin Jones in January 1985.

Indeed, the champion was rumoured to have dropped 21lbs in three weeks ahead of the fight with Honeyghan, with 10lbs coming off during fight week. When winning contests, Curry’s battle with the scales had added to his mystique, defeat turned everything on its head, though; the revisionists insisted that Don had been an accident waiting to happen. That it happened against an unknown and bolshie Brit was too much to bear.

Lloyd, though, was now allegedly $170,000 richer, a figure he later denied, and could add the world title straps to his colourful wardrobe. He had also emulated his idol, Muhammad Ali.

“When I was 12-years-old, I saw Muhammad Ali on television, and I said ‘I want to be like that man, champion of the world’. I watched the tapes (of Curry) twice and gave them to my trainer. I’ve seen enough, I said. He fought the same way. He came straight ahead, and he held his hands up high. When I got inside, I turned on him and there was nothing he could do about it,” insisted Lloyd when speaking to the stunned media.

“I am a quick learner. All the praise people have been giving to Curry, they can now give to me. All the talk coming into this fight was about how good he was. Now it’s my turn to do the talking. I wanted to come over here and get the respect of the American people. I fought a couple times in America before and looked real lousy. I guess that’s one reason they made the fight. Who would take me seriously?” (The Times, 29 September 1986)

Lloyd’s logic was easy to follow; he had beaten The Man so he was now The Man. American fight figures disagreed. “Honeyghan is a good fighter but it is hard to measure how good when he was fighting the ghost of Don Curry,” blasted Curry’s business manager, Akhbar Muhammad (The Times, 1986).

Top Rank’s publicity director, Irving Rudd, was stunned, telling the same publication that: “We knew very little about Honeyghan before the fight and everyone tended to write him off though you can never write off a Mickey Duff fighter. But still it has all been so sudden and stunning that it has thrown all future matches into a cocked hat. We shall put up a couple of suggestions but it is up to Duff to approve.”

Lloyd had kept his side of the bargain, he had been true to his pre-fight claim that he would “Punch his (Curry’s) face in and take his title.” Now came the hard part, convincing the U.S.A. that it was not a fluke, a quest that would bring success, controversy and heartache for Britain’s biggest upset king since Randy Turpin. Certainly, Lloyd was insightful when declaring that his victory would inspire a future generation of British fighters and fans.

“All this stuff is good because young kids look up to me. I don’t drink, smoke or take drugs. The occasional glass of wine doesn’t hurt anyone. Kids these days need heroes and there aren’t many around. They look up to me because I beat a legend. I’m a legend, the undisputed champion of the world,” (The Times, 1986).

There were dissenting voices. It was hard to knock Honeyghan’s in-ring form so his colourful personal life was often cited as a worry. The fighter was popular with women, fair enough when he was a contender, but not quite as acceptable when you become a household name. The tabloids painted him as a wild womaniser, a charge that would dog Lloyd throughout his championship career and which led the boxer to successfully hit The Sun with a libel writ in 1988 after they ran an article entitled ‘Big Headed Honeyghan’ which read as a character assassination.

When hit with the accusations of lasciviousness in the wake of his win over Curry, Lloyd said: “Well, that’s the Press for you. What can I do if they want to print things like that? Sure, I like women, just like everybody else. I love women. There’s no two ways about it. When I was younger, yeah, sure I used to make love, go training, make love, fight and then make love when I’d finished. But now I’m champion of the world, I can’t do that. I’ve got to set an example to young kids. But I’m not reformed. I’m the same Lloyd Honeyghan. I’m not changing for anyone, but I’m world champion now,” (The Times, 1986).

There was always a truthfulness to Honeyghan, his swagger stretched way back to his amateur days, when he was billed as ‘The Master of Disaster’ and used to come to the ring in a swanky, personalised robe. Lloyd was clearly enjoying his time in the sunlight, if not the tabloids. He was honest to a fault, perhaps, but a million miles away from the robotic banality of many major sports stars.

There was even time for a spot of political protest. Honeyghan was ordered to defend his WBA belt against Harold Volbrecht of South Africa. Apartheid was all over the headlines; Lloyd made it clear that he could not countenance the thought of defending against a white South African.

“I would not fight Volbrecht for a million pounds—either here or in South Africa. How could I look myself in the mirror each morning or face my own people on the streets if I agreed?” he declared, although throwing the WBA belt into a bin would require a bit of PR repair work from manager Micky Duff further down the line (The Sunday Times, December 23 1986).

Duff did have immediate plans for his latest champion. American idol Mark Breland was 16-0. Breland picked up the vacant WBA belt by defeating Volbrecht in Atlantic City on February 6 1987. His early paid career had failed to live up to his glittering 110-1 amateur slate but the Brooklyn-raised boxer was highly rated in the U.S. First, though, there was the small matter of Honeyghan’s maiden defence against Johnny Bumphus at Wembley’s Grand Hall, London on February 22.

A former WBA light-welterweight title-holder, Bumphus was an interesting character, the Nashville-based southpaw brought over an exotic entourage member for his first and last welterweight title tilt. Dominic Giacobbe may sound like a character from The Sopranos yet the New Jersey fight figure was not your regular camp member. He was billed as Bumphus’s secret weapon, an expert in meditation who would focus the challenger’s mind and ensure that Lloyd was hit with a dose of instant Karma come fight night.

“We meditate. It is a Zen type of meditation, 2,000 years old. It gives Johnny mental and physical flexibility when the going gets tough,” said Giacobbe when asked about his crucial role (The Times, February 17 1987).

Bumphus had brought the guru into the fold after losing his WBA belt to Gene Hatcher, a future Honeyghan victim, in 1984. Dominic introduced Bumphus to Tang Soo Do; Johnny introduced the concept to his manager Lou Duva and before you know it five of the 1984 Olympic starlets—Meldrick Taylor, Evander Holyfield, Tyrell Biggs, Mark Breland and Pernell Whittaker—were part of the Tang Soo Do crew.

“I knew Dominic could help me when I saw the kind of things he could do like put motorcycle spokes into his arm and hang cans of water on them,” explained the challenger. It certainly made for a strange pre-fight warm-up routine. “We get into the lotus position and focus on a candle and the fire power enters our bodies through the eyes. Concentration gives you internal power—ki—something I learned in the Orient,” revealed Giacobbe.

A deputy sheriff in his hometown of Nashville, Bumphus listed the Smith & Wesson as his favourite firearm only to be undone by a machine gun-like start from Honeyghan, who knocked his man down in the first round before racing out as soon as the bell went for round two and scoring another knockdown at 0.72 of the session. A move that took everyone by surprise—including referee Sam Williams.

Williams was engaged in a tussle with the BBC’s cameraman and barely had time to register the fact that Lloyd had raced across the ring and hit his foe. Lloyd’s rush was within the rules but was deemed not in keeping with the spirit of the sport.

“I felt this tugging at my trouser leg,” recalled a bemused Williams (All the Honeyghan-Bumphus quotes are taken from The Times, March 1 1987). “It was a gentleman from the BBC. He wanted me to move over to the other neutral corner. I was in the way of his camera, I was trying to explain to him that I didn’t think this request was quite appropriate when suddenly out of the corner of my eye, I saw Honeyghan headed across the ring.”

Or as Lloyd famously put it: “The bell went ‘ding’ and I went ‘dong’.” Sam’s take was far more sober. “The offending blow didn’t even land. It didn’t hurt Bumphus. Honeyghan already had destroyed him,” argued the third man, who called a ‘no knockdown’.

Bumphus’s team were upset. They made two things clear. Firstly, they were going to launch an appeal in order to obtain justice. Secondly, Duva insisted that his man would never again step into the ring with Honeyghan. “We only want to see justice done. We’re not going back into the ring against that guy. In fact, Johnny may never fight again,” raged Lou, he was right, Bumphus called it a day

Still, Lloyd’s actions forced the BBBoC to implement the 10-second warning rule. Thereby giving the ref, the fighters and the cameramen an opportunity to brace themselves ahead of the next session.

Not one to be shy with his opinions, Mills Lane—experienced referee, sheriff and Robert Duvall-lookalike—lumped all the blame on Williams, a fellow officer of the law (Williams worked the streets of Detroit as a policeman). “It should never have happened. The referee lost control of the fight and that’s all there is to it,” blasted Lane.

IBF president Bob Lee drew a line under the latest ‘Ragamuffin’ controversy. “I gave him [Honeyghan] a little whisper after the fight. I told him that for his own good, and others, he had better not do it again,” sighed Lee when asked for the IBF’s official ruling on the incident.

It was an eventful first defence, even by Lloyd’s standards; the champion’s rapid response went down in history as one of boxing’s maddest moments whilst the fight itself joined the annals of one-sided beat-downs. Bumphus had been well and truly caught cold—perhaps he was still in a meditative state. It seemed that the British upstart was on his way to showing the entire world that he deserved his place on the P4P list.

A further step towards universal acceptance came during a hard-fought points win over undefeated American challenger Maurice Blocker at London’s Royal Albert Hall on the 18th of May 1987. Lloyd moved to the south of France ahead of the fight only to relocate as the date approached. Honeyghan had ran out of sparring partners—American imports Tony Montgomery and Mike Tynley left Cannes six days early—so the champion headed back to his London stomping ground in search of fresh meat.

“I hired Montgomery to spar not less than three rounds and not more than six, but after a day he would not do any more than two. Tynley decided he was not getting enough money, asked for more, but I told him to catch the next plane home. It could have become serious if we had stayed in Cannes for another five or six days,” marvelled Duff when explaining the decision (The Times, April 2 1987).

Lloyd was soon back on form, drafting in Kirkland Laing and James Cook for sessions. Laing had initially planned to join the champion over in France only to misplace his passport ahead of the trip—par for the course for Laing, himself a mercurial character. Outside the ropes, Lloyd was proving a model champion, literally—Duff netted his charge a six-figure deal with FU jeans ahead of the WBC and IBF title defence.

Honeyghan, however, still had a few more surprises up his sleeve; the 26-year-old subjected the press to the equivalent of his second stanza mugging of Bumphus during a short, 45-seconds, press conference. Lloyd told the massed media that he was going to “surprise everyone”; he then outlined his future plans. “I’m cheesed off with boxing, and if my next fight is not against Sugar Ray Leonard or Duane Thomas, I am retiring,” he announced before exiting stage left (The Times, April 10 1987).

The astonished writers broke the news to Bobby Neill, “He told me something about it last night, but I did not take it seriously,” shrugged the bemused trainer. As build-ups go, it was unusual and resulted in a mixed performance on the night as Lloyd went the 12-round distance for the first in his career.

Worryingly, the Jamaican-born boxer faded as the fight progressed. Bob Miles, trainer of Bumphus, believed that cracks were starting to appear. “I would never have believed that a man with Honeyghan’s frame would start to fade from body shots as early as the sixth round. In the last round, why was Honeyghan, the pressure fighter, running? Did you see the lumps on Honeyghan’s face?” asked Miles (The Times, April 20 1987).

Lloyd did what any Brit would do—he blamed France. He said, “My strategy was right. The only trouble was my fitness. Working in the South of France was a good idea that went wrong. I only managed to spar four times.”

Duff had seen enough, insisting that they would prepare for fights in the U.S. in future. Lloyd was now 30-0, the undisputed force at welterweight and on a ‘Ray Leonard and retire’ mission, his next outing would see him go from the circus of France to a bullring in Spain and, again, the ‘Ragamuffin Man’ made it a night to remember.

The next part sees Honeyghan lose his title, regain a portion of it and finally net that elusive Breland showdown.